chedo

Charters, Samuel, prod. 1975a. African Journey: A Search for the Roots of the Blues. Vanguard, SRV 73014/5.

(Kedo / Chedo)

The word "chedo" is the Fula word for Mandingo, and is pronounced almost as kedo. This great song is widely known among Mandingo singers, and tells the story of the last war between the Fula and the Mandingo in the interior of southern Senegal and Guinea in the 1860's. The war is often called the "war to end war." It began with a squabble between a Fula group and the warriors of Kabo, the Mandingo capital, over the millet crop - "koos" - which the Fula claimed the Mandingo were destroying. The song opens with the Fula complaint that the "chedo" are finishing the koos. As always in a performance by a Jali the song is only the framework for the weaving of comment and moral lesson which thread through the narrative. Few performances go on to describe the war's final holocaust, but as a result of alliances between Moslem Fula groups it took on the character of the religious wars that were ravaging West Africa during this period and the Mandingo were driven back to the royal palace of King Janke Wali. As the Fula warriors stormed the gates Janke Wali ordered his men to let the Fula fill the compound, and as soon as the Fula had jammed in, the powder magazines - seven buildings scattered among the other buildings of the palace - were ignited. The explosion destroyed the entire palace area, killing all the warriors of both sides, the king and his retinue.

The piece is always played with the rhythmic tapping of the forefinger against the short sticks by which the kora is held. The names mentioned are warriors who fought with Janke Wali, most of them part of two fighting groups, the Sannahs and the Mannehs. The line "The bees have gotten into the wine" means that the warriors have gone into battle, and it is the Mandingo women who cry that they don't want to be slaves to the Fula.

Oh Chedo,

Don't finish the coos,

Dont' finish the coos, you Sanneha [sic] and Mannehs.

You people listening to me,

War is no good, it is filled with death.

Men lie dead without burial, friends kill each other,

they see friends dying.

You people don't know, Kabo is filled with warriors,

the Sannehs and Mannehs.

Who is the king in Kabo?

The king is Janke Wali.

Listen to Sani Bakari coming, the war is going badly,

Listen to Sani Bakari, standing up, ready to fight again.

With love there must be trust,

if you love someone they must be able to trust you.

Knowing someone also brings about sorrow.

Now I love men who refuse me things and go on refusing.

Oh, this world,

many things have gone and passed,

the world wasn't made today and it won't end today.

All these things happened in the reighn of Janke Wali.

Oh grand Janke Wali, and Malang Bulefema, together with

Yunkamandu, Hari Nimang, Lombi Nimang, Teremang Nimang,

Kuntu Kuntu, Nimangolu.

If you hear the word "Nyancho" it means Sanneh and Manneh,

the word "koringolu" means Sonko and Sanyang.

Katio Kati Mangbasani, Pachananga Dela Jenung,

Sanneh Balamango, Ding Kumbaling Fing.

The bees have gotten into the wine,

these that eat good meat and drink good wine,

the Sannehs and Mannehs. . . . . .

(repeats the names of the warriors)

The karingolus all have died.

Hear the cries of a lazy woman who is saying "The birds are

eating all my rice, I'll have to look for another place to go."

You don't know what it was like the day they were crying

for Malung to come out and fight.

It was a fierce, fearful day.

"Yungkamandu, come out and fight."

You men who are ready to die today,

you must come out and meet the other warriors.

Days like these were never good.

The wars in Kabo were very fierce.

These were the days of killing.

"Oh uncle, we don't want to be slaves to the Fulas."

(instrumental bridge)

Quarreling every day ends love.

Oh this world,

the world that wasn't made today and won't end today. . .

Knight, Roderic. 1982a. "Manding/Fula Relations as Reflected in the Manding Song Repertoire." African Music 6 (2): 37–47.

(Chedo)

p. 39

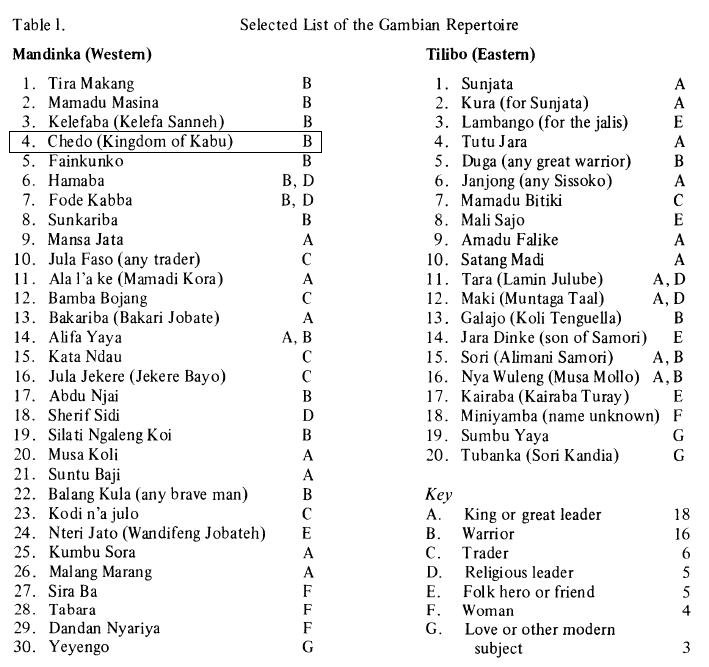

Table One . . . includes the best known, most often heard, or otherwise significant songs in the [Gambian] repertoire. In each column the top few songs are the oldest, and the bottom few are the youngest. The majority in each case fall somewhere in between (often in the nineteenth century), but no chronological ordering beyond this is intended, since it is often not possible to date a song exactly. Most of the songs bear the name of their owner as the title. Where they do not, his name is shown in parentheses next to the title. The letter code at the right represents the person's "claim to fame" or calling in life, as shown in the bottom of the list.

p. 40

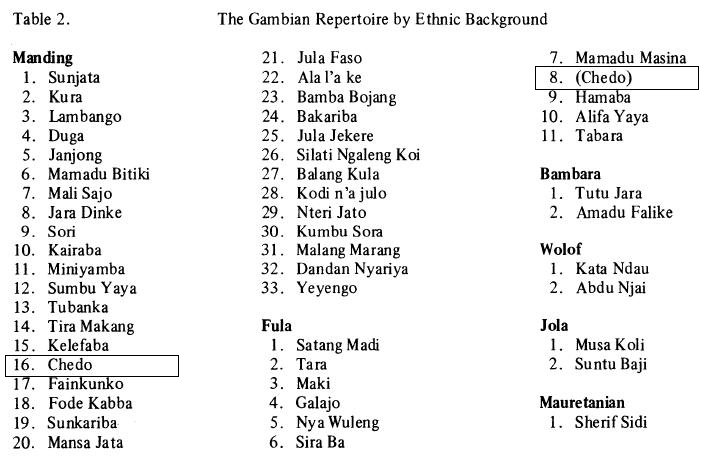

Table Two shows the same fifty songs again, grouped this time by the ethnic background of the people commemorated.

p. 41–43

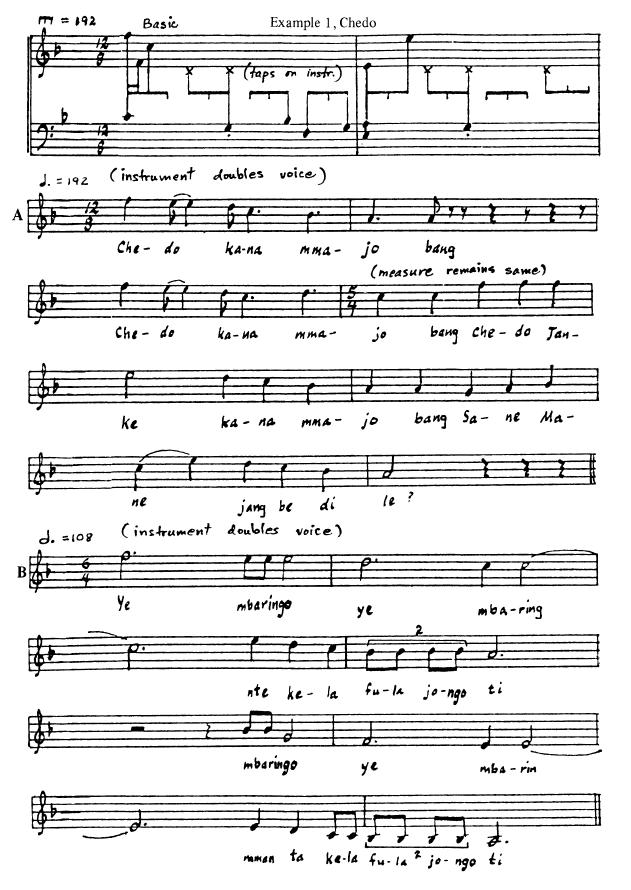

It was a group of Fula in Kabu that objected to the spoiling of their millet crop by the renegade horsemen of the Mandinka, who, in addition to trampling it, were using it for kindling. This objection became the opening line of the song entitled Chedo, which is one of the Fula words for the Mandinka. It says "Mandinka, don't spoil my millet. If you do I will be forced to return to Firdu and the war has already driven me from there" (See Example 1A). The rest of this song is about the war between Futa and Kabu, which began as a civil war between the Islamic Mandinka and their pagan Mandinka rulers. The Fula settlement of Kabu joined on the side of Islam, eventually involving the Futa Fula to destroy Kabu in 1867 (Moreira 1948). The resolve of the pagan Mandinka warriors against their adversaries is characterized in other words from Chedo: "The slave of a Fula I will not be" (Example 1B).

1A

| Chedo kana m majo bang | Mandinka, don't spoil my millet |

| Sane Mane jang be di le? | Sanneh and Manneh, how is it here? |

1B

| Ye, mbaringo, ye, mbaring | Oh, uncle, oh, uncle |

| Nte kela Fula jongo ti | I won't be the slave of a Fula |

| Mbaringo ye, mbaring | Oh, uncle, oh, uncle |

| M man ta kela Fula jongo ti. | I'm not going to be a Fula's slave. |

Jessup, Lynne. 1983. The Mandinka Balafon: An Introduction with Notation for Teaching. La Mesa, Calif.: Xylo.

(Chedo)

pp. 146–59 (Appendix 2: Balafon Repertoire)

| Title | Chedo |

| Translation: | "Mandinka" in Fula language |

| Dedication: | Kingdom of Kaabu, Janke Wali |

| Notes: | Wali was a Fula |

| Calling in Life: | Warrior |

| Original Instrument: | Kontingo |

| Region of Origin: | Manding (Western Coastal Region) |

| Date of Origin: | M (19th & 20th c. up to WWII) |

| Sources: | 1, 3 (Jessup & Sanyang, R. Knight 1973) |

Knight, Roderic. 1984. "The Style of Mandinka Music: A Study in Extracting Theory from Practice." In Selected Reports in Ethnomusicology, vol. 5, Studies in African Music, ed. J. H. Kwabena Nketia and Jacqueline Cogdell Djedje, 3–66. Los Angeles: Program in Ethnomusicology, Department of Music, University of California.

(Chedo)

p. 10

In performances of "Chedo," a song about the famous nineteenth-century Mandinka kingdom of Kabu in present-day Guinea-Bissau, it is still common to include passages that represent the galloping of horses and the circling of vultures overhead.

Kouyate, M'Bady, and Diaryatou Kouyate. 1996. Guinée: Kora et chant du N'Gabu, Vol 2. Buda, 92648-2.

(Ke Do)

Ke Do means Mandingo in Fulakunda. After the Kansala war, this song was sung by Jali Wali and dedicated to Dianke Wali Sane, Kansala's heroic defender.

Suso, Jali Nyama. 1996. Gambie: L'art de la kora. Reissue of 1972 with other unreleased material. OCORA, C 580027.

(Cheddo)

"Cheddo" is a Fula term meaning "pagan renegade". The song is one of the most prized chosan tunes in jaliyaa. It is about the siege of Kaabu, a pagan Mandinka kingdom, by the Muslim Fula people of the Fouta Djalon mountains, in about 1865. Prior to the battle, enclaves of Muslim Mandinka in Kaabu had been engaged in disputes with their pagan leaders for some time when they enlisted the aid of their Muslim neighbors, the Fula. The Fula armies mounted a siege. After extensive fighting, it became clear to Janke Wali, the pagan king of Kaabu, that the invading forces were too great to repel. He allowed the armies to surge into the Kaabu fort and then ordered six powder magazines exploded, killing everybody in the fort, himself included. For this reason the war is called the turubang kelo—the war to end even the seeds of the future—and the Kaabu warriors are singled out as the bravest the Mandinka have ever known.

"Cheddo" may be played in tomorabaa or tomora mesengo, or as heard here, Nyama's personal variant that combines somes [sic] features of each. An essential part of the performance of "Cheddo" is a technique called bulukondingo podi, in which the player flicks his right forefinger against the hand grip of the kora, producing a resonant knock.

"Warrior princes, you who understand shame, look at this! [Praise for the Sanneh name]: Suma Tamba Dark, Suma Tamba Light, Kanku Tamba and Maran Tamba / Ah, in those days they killed you quickly, tied you tightly, sold you outright / Those days are gone forever, the days of Janke Wali / Ah yes, if you hear nyancho, that means Sanneh and Manneh; koringo, that means Sonko and Sanyang / The never-to-be shamed warriors are gone // Cheddo don’t spoil my millet, ah King Janke Wali, don’t spoil my millet [This is a complaint by the Fula that the Mandinka were using their millet for kindling.] / Don’t you know, war is not sweet: the strong man can die there and go without a grave // On that day the warrior's wives cried, saying they would never submit to life under the Fula / Ah, my uncle, able warrior [On the kora, the sound of galloping horses.] / Ah, the warrior's wives wore elegant coiffures, something to behold but not to touch, intertwined with silver and gold."

Kouyaté, Sory Kandia. 1999. L'épopée du Mandingue. Mélodie, 38205-2. Re-issue of 1973, SLP 36, SLP 37 and "Toutou diarra" from SLP 38.

(Kedo)

Chanson épique des seigneurs de guerre de Kabou (Casamance et Iles du Cap Vert). On y parle d'un guerrier célèbre qui fut un bon soldat, un diplomate, un notable généreux.

Charry, Eric. 2000. Mande Music: Traditional and Modern Music of the Maninka and Mandinka of Western Africa. Chicago; London: University of Chicago Press.

(Chedo)

pp. 44–45

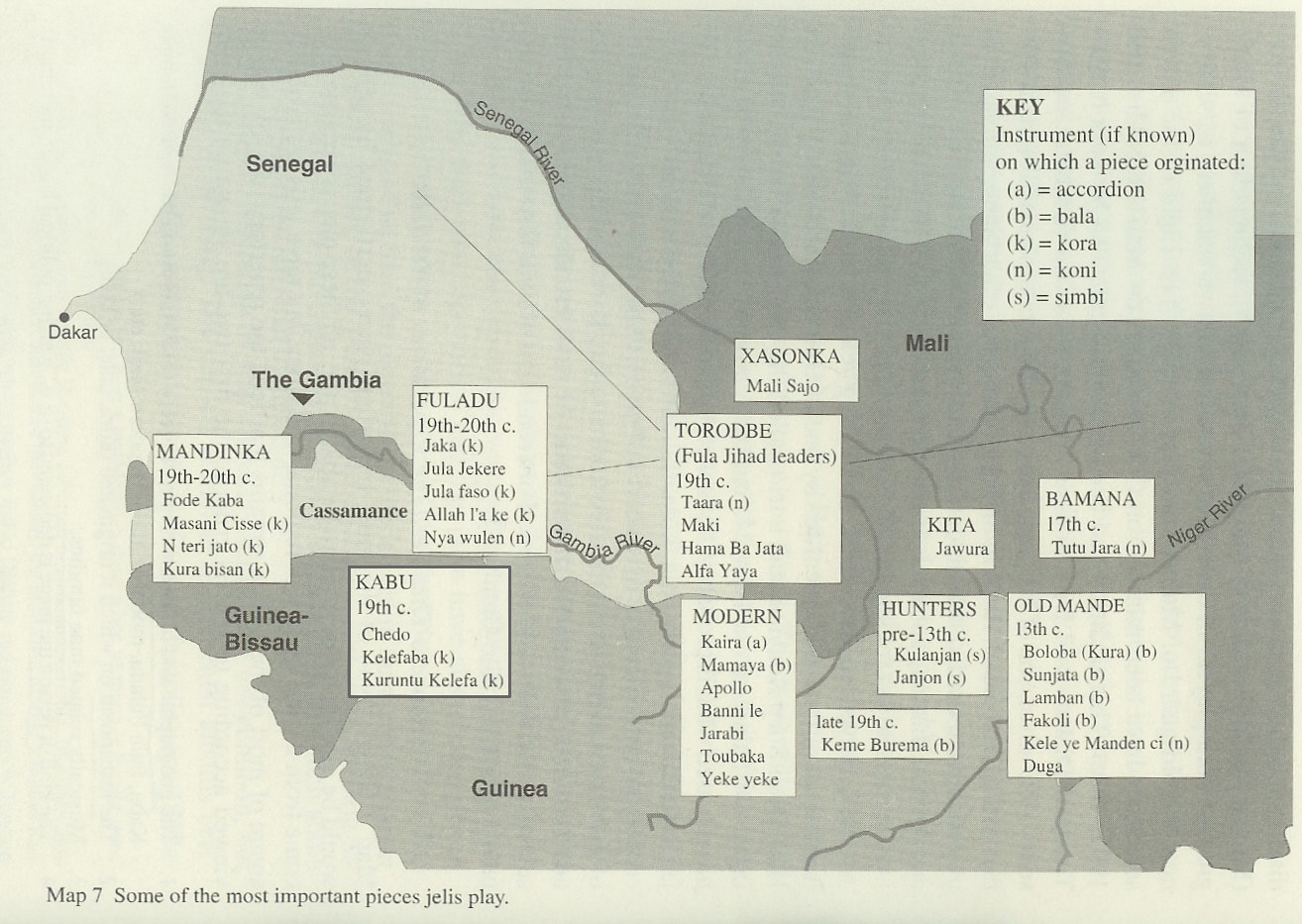

With the decline of Mali in the mid-fifteenth century these states [that paid tribute to the king of Mali] joined into a confederation that came to be known as Kabu (Gabu or Ngabu), which ruled from its base in Kansala (in present day Guinea-Bissau). Senegambian Mandinka jalis maintain oral traditions about the Kabu empire, usually rendered in a piece of music called Chedo (Fr: Tiedo), primarily concerned with the dramatic downfall of the empire in the mid-nineteenth century. Oral traditions show little concern for the several centuries between the initial rise of Kabu and its demise.

The demise of Kabu is attributed to an argument over succession to mansaba between the Sama and Pacana provinces [in the eastern region of present-day Gambia, Senegal, and Guinea Bissau]. When Janke Wali Sane of Pacana finally rightfully became ruler about 1850 he made three predictions (mansa daali): a war would break out between Kabu and the Futanke (Fulbe from Futa Jalon); the fortress at Kansala would be called turban (hecatombe—the end of life in Kansala); and he would be the last king of Kabu. The defeated Sama province enlisted the aid of Fulbe from Futa Jalon to exact revenge. Their efforts were successful in part because of Fulbe resentment that the Mandinka were exploiting them and pillaging their animals and millet crops. In the piece Chedo, Mandinka jalis recount the exploitation of the Fulbe and tell of the ensuing siege of the fort of Janke Wali at Kansala, the capital of Kabu.

About 1865 the turban kelo (Kansala war) broke out (Mané 1978: 142–45). The Futanke laid siege to the Kansala fortress. Sensing defeat, Janke Wali made plans for the escape of his jali, Jali Wali Kouyate, who refused to flee. Janke Wali ordered the gates open, and when the Fulbe entered he set fire to his ammunition cache, blowing up the fortress and killing everyone. The Mandinka women are said to have committed suicide in the wells of the town rather than submit to Fulbe slavery.

After the fall of Kansala, Alfa Molo Balde led a Fulbe revolt in 1867 and took over much of Fuladu (in eastern Gambia). Alfa Molo died about 1881 and was succeeded by his brother Bakari Demba and son Musa Molo, who ruled until 1919 when he was exiled by the British to Sierra Leone. Musa Molo is a major figure in the oral traditions of eastern Gambian jalis and was an important patron for them.

p. 148

p. 156

Chedo (Fr: Tiedo) or Kedo, the name given to a certain class of warrior during the time of the Kabu empire, is used as a vehicle for recounting the history of the empire. The Archives Culturelles in Dakar has commissioned many field recordings of it in the course of their research into oral traditions of the Casamance. Chedo, like Sunjata, has also been adapted by popular singers such as Ismael Lo (1985-disc) and Baaba Maal (1994-disc). Chedo most likely comes from the kora or koni.

pp. 398–401 (Appendix C: Recordings of Traditional and Modern Pieces in Mande Repertories)

Unidentified Instrumental Origin: Chedo/Kedo

Unidentified (Guinea Compilations 1962a)

Jali Nyama Suso ([1972] 1996)

Sory Kandia Kouyate ([1973] 1990)

Ismael Lo (1985)

Sunjul Cissoko (1992)

Ifang Bondi (1994)

Baaba Maal (1994)

Morikeba Kouyate (1997)

Farafina (1997)

Eyre, Banning, prod. 2000. In Griot Time: String Music from Mali. Stern's Africa, STCD 1089.

(Kedo)

The song, sometimes called "Tiedo," is a classic, and tells the story of a brutal conflict between two societies in the province of Cassamance, in southern Senegal. In the end, both armies were destroyed, and the only living thing that remained was a baobab tree.

Fula Flute. 2002. Fula Flute. Blue Monster.

(Chedo)

Piece from Gabu celebrating the King Janke Wali. It is unusual for a Fulani to play this because Janke Wali was an enemy of the Fulanis of the Fouta Djallon who defeated him in battle.

Jobarteh, Dembo. 2003. Listen All. CD Baby.

(Cheddo)

A traditional dating [sic] back to the times of slavery.

Ba Cissoko. 2005. Electric Griot Land. All Other/ 3D Family, 5101124392.

(Tjedo)

This title is a traditional song of the griots' repertoire, written in the honour of a king of Gabou in Guinea Bissau. A hommage, written by his griot, to kind Djanke Wali Sane, a great warrior chief, who fought and defeated the Peulhs during the Soundiata Keita era, that is, at the end of the 13th century.

Diabate, Madou Sidiki. 2006. Traditional Kora Music from Mali. System Krush/Ascap, CD006.

(Chedo de Kabu)

Chedo (Che: man, do: some) is from the city-state of Kabu in what was the Kingdom of Jolof and is now Guinea-Bissau. It was first dedicated to Kabu warriors who repelled an attack by the Fulani. It is now used to praise the brave, and people of power, though never women.

see also:

Innes, Gordon. 1976. Kaabu and Fuladu: Historical Narratives of the Gambian Mandinka. London: University of London School of Oriental and African Studies.

Mané, Mamadou. 1978. "Contribution à l'histoire du Kaabu, des origines au XIXe siècle." Bulletin de l'IFAN, ser. B, 40 (1): 87–159.

Sembène, Ousmane, dir. 1977. Ceddo. Films Domireew. Reissued in 2005. New Yorker Video.