sörsörnë

Africa Soli. 1992. Salya: Roots and Rhythms from Guinea. Sango Music, CD SM007.

(Bandafeleko)

Popular chant from maritime Guinea (the region of Boke). A man in love calls his sweetheart and invites her to the festivities in the village.

Keita, Mamady. 1992. Nankama. Fonti Musicali, FMD 195.

(Sorsornet)

Région: Boke. Rythme: Baga (no. 5 on map.)

Rythme populaire chez les Baga, chanté par les jeunes filles au clair de lune lors de l’initiation, mais également après la récolte, pour remercier leur maman.

| M'baraka felenkoee N'doro mamuna komna M'baraka felenko n'gayo n'gaa N'doro mamuna komna N'tapelindoee, n'tapelindoee. N'tapelindoee zinezagona banganiee |

Merci, ma mère. Merci de m'avoir donné un personnalité. Ne te fâche pas, bientôt je m'en irai chez mon mari. |

Lamp, Frederick. 1996. Art of the Baga: A Drama of Cultural Reinvention. New York: Museum for African Art and Prestel Verlag.

(Sörsörnë)

pp. 204–8

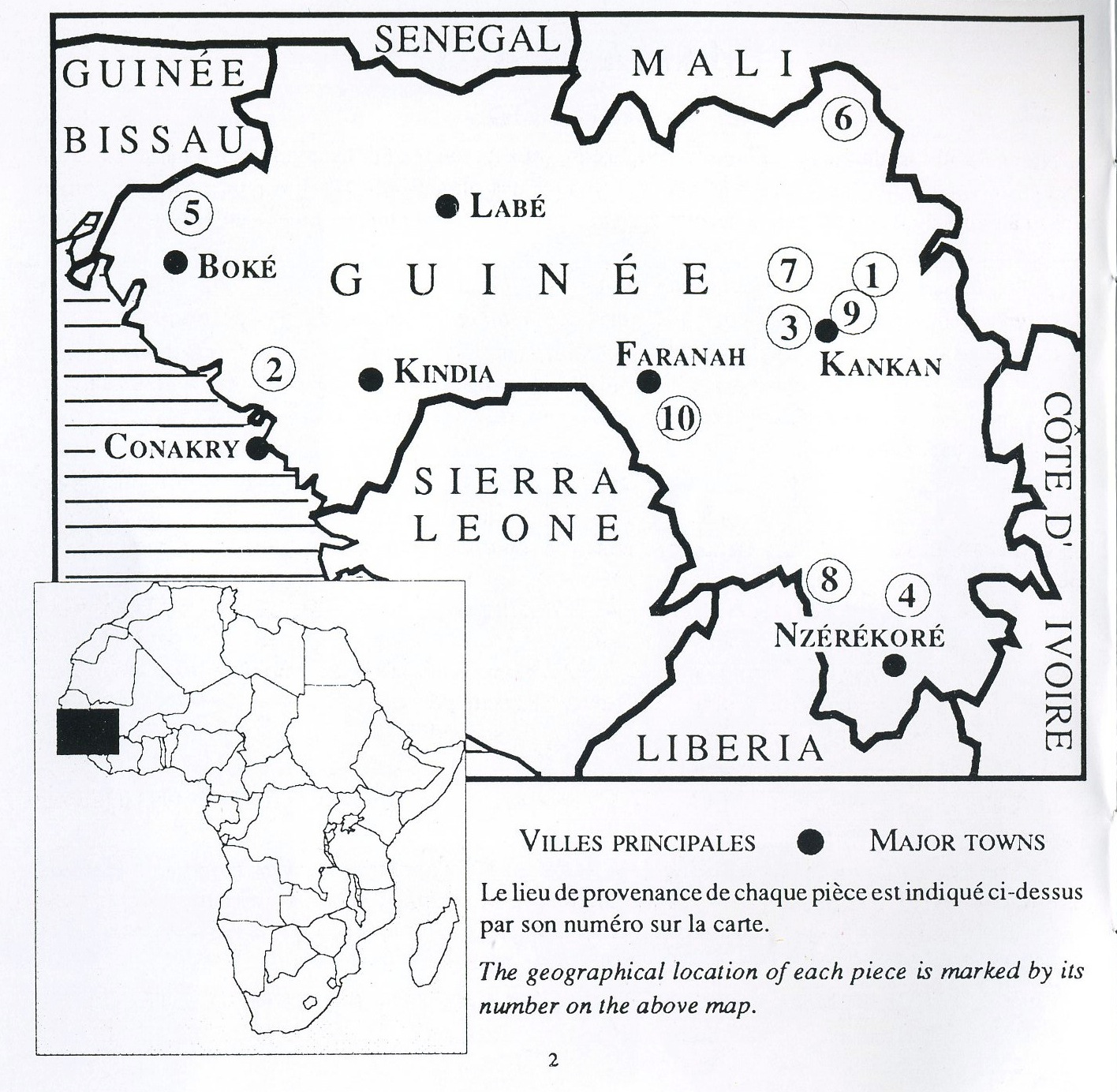

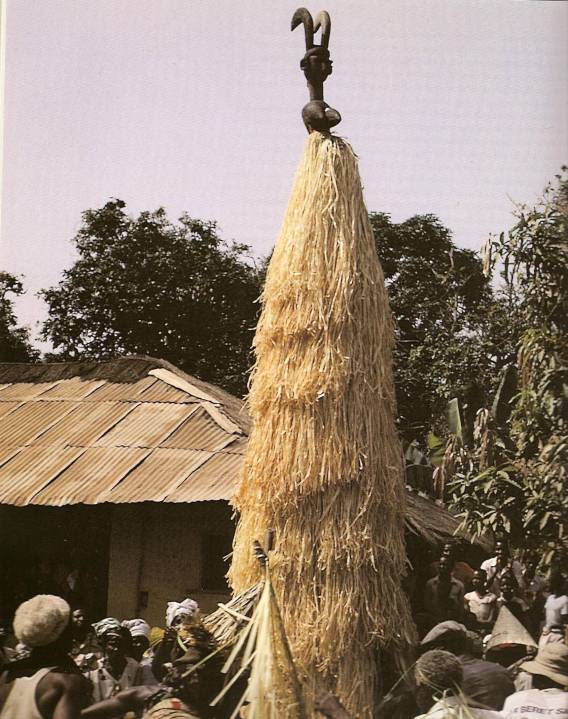

Dance of Sörsörnë, Baga Sitemu. This is the masquerade [. . .] before rising up. Photo: Frederick Lamp, 1987.

The essential feature of Sörsörnë is a tall raffia dress. This garment is usually surmounted by a headdress in the form of a female bust with short vertical horns, but the headdress is not a constant. By one account we heard, elder men born around the turn of the century claim to have introduced Sörsörnë in their youth, at Tolkotsh. Unlike all other inventions by Baga youth of this century, the songs of Sörsörnë have no Susu lyrics, but are exclusively in Baga. The name Sörsörnë itself is derived from the word sörnë, meaning "to heighten."

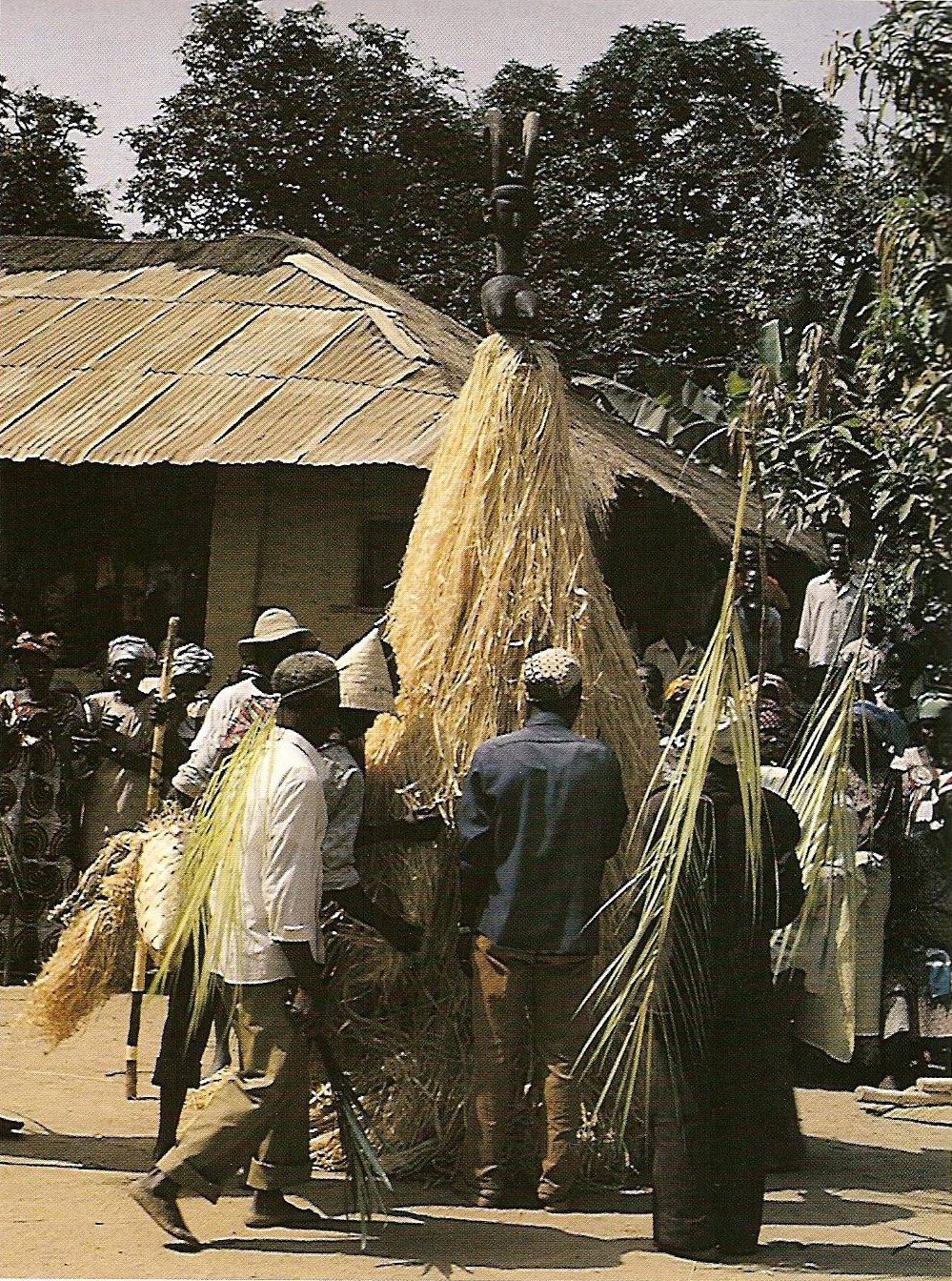

In the dance, the costumed figure first appears at somewhat above a man's normal height. Then it grows taller and taller throughout the performance, until it sometimes reaches the level of the branches of the full-grown coconut palm. The single male dancer beneath the raffia dress is said to hold a telescoping set of bamboo tubes by which he elevates the costume's top. But children don't know this, and are enthralled; and if the general public does know, that in no way diminishes the theatrical effect of seemingly supernatural transformation.

Through an hour or so of movement, the figure moves up and down several times and circulates slowly around the village's central plaza, swaying back and forth. A group of young men always clusters around the costumed dancer, helping to steady the structure if necessary, and guiding his movements. A leader of this group speaks loudly to Sörsörnë, exhorting him to "rise up, rise up":

The woman who would see this spirit—if she couldn't have a baby, would have one. When the spirit wishes, it can be as tall as the sky. If it wishes, also, it can come as low as the ground. You see it seated now. It brought this palm wine that we are collecting now. Come down, come down. . . . Go up, go up. I want to see how tall you can go.

Dance of Sörsörnë, Baga Sitemu. This telescoping masquerade is the invention of the youth, appearing dangerously similar to the highly prohibited supreme male spirit of the elders. Photo: Frederick Lamp, 1987.

The horned female bust that today often surmounts the costume is of a type [. . .] called Tiyambo. There are versions of Sörsörnë, however, without this headdress, but only a set of horns—perhaps the secondary essential element. No reference to Sörsörnë appears in any published literature, and indeed not a single manuscript reference appears before 1990 outside my own field notes. A photograph taken in 1985 in Katako seems to be the earliest available. So we have no idea what was incorporated in early examples.

As in the monologue quoted above, an association is made between Sörsörnë and the collecting of palm wine—always a task of the young men. In ritual, the young men must supply palm wine to the old men. One song links Sörsörnë's origin with the village of Kaklentsh, a major source of palm wine for the Baga Sitemu:

| Sörsörnë—mä pe-o, mä tör-o Sörsörnë | Sörsörnë—Go up, go down, Sörsörnë |

| Sörsörnë, ö de mä yëfë-e | Sörsörnë, where do you come from? |

| Kaklentsh mä yëfë Kaklentsh. | You come from Kaklentsh. |

As a masked spirit of the young men, Sörsörnë naturally operates in a milieu of defiance and cheek. One of its most popular songs asserts a youthful in-your-face challenge to those who would attempt to enter their celebration unauthorized:

| a to-lom to-su | Our sacred masked dance— |

| kö mä fañ pi kä näñk-e | If you want to see it |

| mänë mä wurë tondu pa näñk | You have to show your ass. |

| o-wololo | Good grief! |

According to Vincent Bangoura [. . .], organizer of the dance group in Katako, Sörsörnë was invented by the elders when they were young, and has been passed to the youth of today, with some breaks in tradition. The essential feature in his story is the creation of the ritual by the youth, the abandonment of this powerful tradition by the youth once they became adults (age grades did not transfer the ritual to succeeding grades), and the reinitiation of the tradition by successive generations of youths. Bangoura compares this history to that of the highest male and female spirits of the Baga, accessible only to fully initiatied adults under the control of the very eldest men:

It was the old [generation] who created Sörsörnë and they have entrusted it to the young, because they [the young] were not permitted to dance the a-Mantsho-ño-Pön, nor the a-Bol; it was reserved for the youth before being initiated to a-Mantsho-ño-Pön and to a-Bol. . . .

Sörsörnë is a sacred masked dance handed down from our forefathers. It was meant for the young people and it had a particular role. Each time it appeared, it rained heavily over the course of a year, there was a good harvest, the kola trees produced abundantly. The year was a year of abundance. The sterile women became fecund.

But later they forgot Sörsörnë; they abandoned it when they became occupied with a-Bol and a-Mantsho-ño-Pön and a-Mantsho-ña-Tshol. When they abandoned it, there was no longer a good harvest, the fecundity stopped, the kola trees no longer produced much. It was then that our Spirit [Sörsörnë] went to consult our ancestor to demand what was happening. . . . So the ancestor of the village called a meeting of all the citizens. When they had convened, he recounted to them what had come to pass. . . . One of them declared that they should all go to the stone where their ancestors conducted sacrifices, and divine with kola nuts, as they did. . . . He who had the kola tossed it in divination, and determined that the declaration of the elder was right and that the Spirit had spoken to him saying that because they had abandoned it, there was infertility of the land and sterility.

Having seen and being satisfied with their discussion with the Spirit, they took the decision to go immediately to conduct the ritual of Sörsörnë. That year, it rained heavily. . . . Since then, they never forgot Sörsörnë until the coming of Asekou [the conversion to Islam in the 1950s].

A third generation, led by Vincent Bangoura, took up the ritual of Sörsörnë again in the 1980s, after the overthrow of the repressive government of Sekou Touré and the loosening of religious restrictions.

It is interesting that Bangoura's text posits a generational tension between the followers of Sörsörnë and those of a-Mantsho-ño-Pön. Those who dance Sörsörnë may not dance a-Mantsho-ño-Pön; those admitted to the circle of a-Mantsho-ño-Pön abandon Sörsörnë. The key factor is generation. Each ritual is exclusive of the other. Uncannily, the figure of Sörsörnë in several respects resembles the figure of a-Mantsho-ño-Pön, the greatest sacred and prohibited male spirit of the elders. This is almost too frightening to contemplate, as the parody or unauthorized representation of a-Mantsho-ño-Pön is forbidden on pain of death (a threat that has been carried out in the past, if testimony is correct.) No Baga consultant, young or old, would confirm this resemblance, yet the resemblance is clear. We saw the same sacrilege in our discussion of the masquerade of the little boys' age grade, and we see it here again with the youth.

If the youth were asserting their defiance of the elders and their right to spiritual power, it is not surprising that they might appropriate existing imagery. Like a-Mantsho-ño-Pön, Sörsörnë, at its height, is as tall as the palm tree, and has a huge, bleached costume of leaves. At its summit is not the avian head of a-Mantsho-ño-Pön (though that too may in some cases be horned) but horns sprouting from the head of a woman. A young man's introduction to a-Mantsho-ño-Pön, the culmination of his initiation into manhood, was a prerequisite to his right to take a young woman as his wife—the right to fulfill a young man's desire. Sörsörnë, then, replaces the avian-headed colossus, the figure of patriarchal sanction, with a figure of legerdemain surmounted by an image of the object of desire itself, the young woman.

Unlike a-Mantsho-ño-Pön, who is always monumental, Sörsörnë occupies the realms of both the low and the grand, and enters one or the other on the will of the young man dancing. It is thus a usurper of traditional power to which it is not entitled, yet it holds this power in defiance, through the institutionalized right of the young to subversion. While the elders have legitimate control, the youth have power by virtue of their willingness to rise up and seize it, by virtue of their desire. During the colonial period as before it, this youthful seizure of power was engrained in the Baga social system.

p. 262

Sörsörnë — masquerade with fiber costume and wooden headdress resembling Tiyambo, used by youths (lit., "Rise up, rise up")

Tiyambo — masquerade with female bust headdress with horns

Koumbassa, Youssouf. 1999. Wongai: Let's Go! Vol. 2. New York, NY: B-rave Studio/Youssouf Koumbassa.

(Sorsoner)

Sorsoner is coming from a village called Boké. Baga people live there. It's an initiation dance for young people.*

* Transcription mine.

Charry, Eric. 2000. Mande Music: Traditional and Modern Music of the Maninka and Mandinka of Western Africa. Chicago; London: University of Chicago Press.

(Sorsorne)

p. 22

Baga rhythms such as Sorsorne and Kakilambe (the Susu term for the highest Baga deity) have entered into the repertory of the national ballets, . . .

Wofa. 2001. Wofa! "Iyo" Live. Guinea: A Concert of Percussions. Buda.

(Boké Gbé — rythme Sönsorné)

Langue Soso.

M'ma wouyama sönö ala khan n'na tanga yakhounyédéma

M'ma wouyama é

Wo toulimati, wo yamasa, wo désokhou

La guiné di é yo, Wofa fayiraba ma di

Afrique di é yo, doubé bara yabi é m’ma

Bangoura, Mohamed "Bangouraké." 2004. Djembe Kan.

(Sorsonet)

From the Boké region.

This rhythm is from the Baga people. It is a song for children. The children sing this song at the time of their initiation. They sing to thank their mothers for giving them life and bringing them up to develop their personalities. They sing to their mothers to not be angry because soon they will be married and leave the home.

Billmeier, Uschi. 1999. Mamady Keita: A Life For the Djembe—Traditional Rhythms of the Malinke. Engerda, Germany: Arun-Verlag.

(Sorsornet, also called Sornet)

Traditional Ethnic Group: Baga; West Guinea, Boke region

Over the course of time, some masks that were seen as bringers of good luck gained ever more favor with the people, until they were considered to be almost deities, as is the case with the mask Sorsornet.

Every once in a while, those masks are taken out to be shown to the people in the village. They are not kept in the village but outside in the woods.

The mask Sorsonet [sic] belongs to a group of people, and when one tries to penetrate its secret, he will inevitably encounter resistance from them. It is a mask against evil. Sorsornet is revered as protector of the village.

If someone has a severe problem (such as an illness or childlessness), he goes to the guardian of the mask, who then goes to find the mask. This can happen approximately two or three times a year.

When the mask is inside the village, the rhythm Sorsornet is played and the mask moves through the village.

Today, Sorsornet is also a popular rhythm to which men as well as women dance.

Camara, Alkhaly. 2004. Xylophone Masters: Guinea; Alkhaly Camara, Vol. 1. Marimbalafon, MBCD001.

(Felenko)

Chanson en l'honneur de l'ethnie Baga, composée par Momo Wandel Soumah, tropettiste, orchestre Keletigui Tabourni [sic].

Keita, Mamady. 2004. Guinée: Les rythmes du Mandeng. Vol. 2. Fonti Musicali, FMU 0320.

(Sorsornet)

Sorsornet is the name of a mask in the region of the Baga people in and around the city of Boké. This mask protects the village and deposes bad spirits. It is kept guarded in the forest and is brought out from time to time when someone has a very serious problem, like illness or sterility. The rhythm took on the same name as the mask. People will dance around Sorsornet as it walks through the village.*

* Transcription mine; of English-language DVD narration.

Camara, Alkaly. 2005. Alkaly Camara: Master Balafonist Vol. 1. Dununya, 2395.

(Felenko)

This is a Baga dance whose song was made popular by Les Ballets Africains's production, "Heritage."

Camara, Naby. 2007. Lagni-Sussu Kanteli.

(Sorsonet)

A Wasulon and Baga rhythm popularized by Les Ballets Africains.

Camara, Naby. 2010. Balaphone Instruction. Vol. 1. Earthtribe Percussion.

(Sorsenet / Sorsonet)

From the Baga people of West Guinea. Sorsonet is played to accompany a powerful mask of protection and healing. It's also a popular dance rhythm played for celebrations.

Delbanco, Åge. 2012. West African Rhythms. Charleston, SC: Seven Hawk.

(Sorsoné)

Mask dance from the Baga people of the Boke region in coastal Guinea.