tutu jara (bajuru)

Ministère de l'information du Mali. 1971. Première anthologie de la musique malienne: 5. Cordes anciennes. Barenreiter Musicaphon, BM 30L 2505.

(Toutou)

This song is virtually the tune dedicated to greatness. All the Mandingo kings were fond of it, for it is only played for a king.

Ministère de l'information du Mali. 1971. Première anthologie de la musique malienne: 6. Fanta Damba: La tradition épique. Barenreiter Musicaphon, BM 30L 2506.

(Toutou)

In the Bambara and Malinké countries, this song is the sign of royalty.

Knight, Roderic, prod. 1972. Kora Manding: Mandinka Music of The Gambia. Ethnodisc, ER 12102.

(Tutu Jara)

Tutu Jara is a song dedicated to one of the kings of the Bambara of Segou, a descendent of their most famous leader, Da Monzon. It was played originally on the kontingo and is best suited to Sauta tuning, which is used here.

Charters, Samuel, prod. 1975a. African Journey: A Search for the Roots of the Blues. Vanguard, SRV 73014/5.

(Tutu Jara)

This song is a well known story about a woman who wants to have a child but has to ask a snake for help.

(Boloba)

p. 220

Sara, Toutou, Kala sont des airs galants dont il est difficile de préciser la date dans le temps.

Jobarteh, Amadu Bansang. 1978. Master of the Kora. Eavadisc, EDM 101.

(Tutu Jara)

Tutu Jara is one of the oldest pieces in the repertoire, and is described as a 'big tune' (juluba), that is, a tune fit to sing the praises of a truly great person. Its text tells the story of a Malian princess who had had a number of stillborn children. During her next pregnancy she made a wish to a snake (tutu) to spare her this child. Her prayer was answered, and she gave birth to a boy, whom she named after the snake.

This is originally a piece for kontingo, and its angular melody is in many ways unidiomatic to the kora, In spite of this it has become a vehicle for Amadu's virtuosity. He is often requested to play it, and performances can last for an hour or more, since it is his patron's favourite tune. Here he plays it as an instrumental solo, based on three different themes. The first constitutes the standard way of playing Tutu Jara and alternates between duple and triple time; the second (introduced after four minutes and five seconds on this track) is supposedly the oldest version, while the third (after five minutes and forty seconds) is Amadu's own composition.

Tutu Jara is played in Sauta tuning.

Konte, Alhaji Bai, Dembo Konte, and Ma Lamini Jobarteh. 1979. Kora Duets by Alhaji Bai Konte and Dembo Konte and by Dembo Konte and Ma Lamini Jobate. Folkways. FW 8514.

(Tutu Jara)

Alhaji Bai Konte and Dembo Konte play an ancient tune from Mali commemorating a king named Tutu Jara. Predating the kora, the song was originally accompanied by kontingos, the small plucked lutes played by Mandinka musicians. Bai Konte has wrought many new variations of the traditional tune.

Durán, Lucy. 1981. "Theme and Variation in Kora Music: A Preliminary Study of 'Tutu Jara' as Performed by Amadu Bansang Jobate." In Music and Tradition: Essays on Asian and Other Musics Presented to Laurence Picken, ed. D.R. Widdess and R. F. Wolpert. 183–96. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

(Tutu Jara)

p. 183

'Tutu Jara' is one of the most important tunes in the traditional upper-river repertoire.

pp. 185–86

Of the four heptatonic tunings used on the kora, only the one known as sauta will be given here since it is the tuning commonly used for 'Tutu Jara'.

Amadu Bansang shows a general preference for this tuning, and certainly the sharp fourth (the only note which distinguishes the sauta from the hardino (tuning) figures prominently in his 'Tutu Jara';6 some other players however, appear to play 'Tutu Jara' in the hardino tuning.7

pp. 187–95 (III. 'Tutu Jara' and its rôle in Amadu Bansang's repertoire)

(See Durán, 1981.) (Transcriptions and analysis.)

p. 187

'Tutu Jara' is considered one of the oldest and most prestigious pieces in the Tilibo repertoire. It may be used to accompany any improvised text16 in praise of the musician's patron, or some other important person. Its own text, from which the title is derived, concerns a princess who, as her children were always stillborn, prayed for help to a snake (tutu). When her next child lived, she named him after the snake to show her gratitude, Jara being the child's second name.

p. 188

'Tutu Jara' was originally a kontingo piece, though it has today become a standard part of the kora repertoire.

Knight, Roderic. 1982a. "Manding/Fula Relations as Reflected in the Manding Song Repertoire." African Music 6 (2): 37–47.

(Tutu Jara)

p. 39

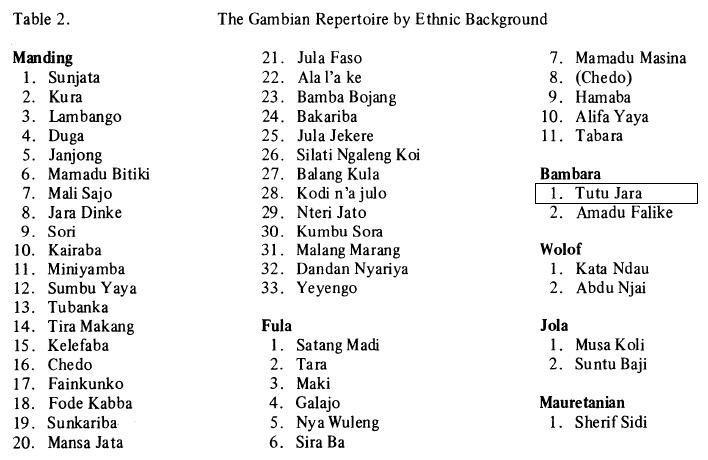

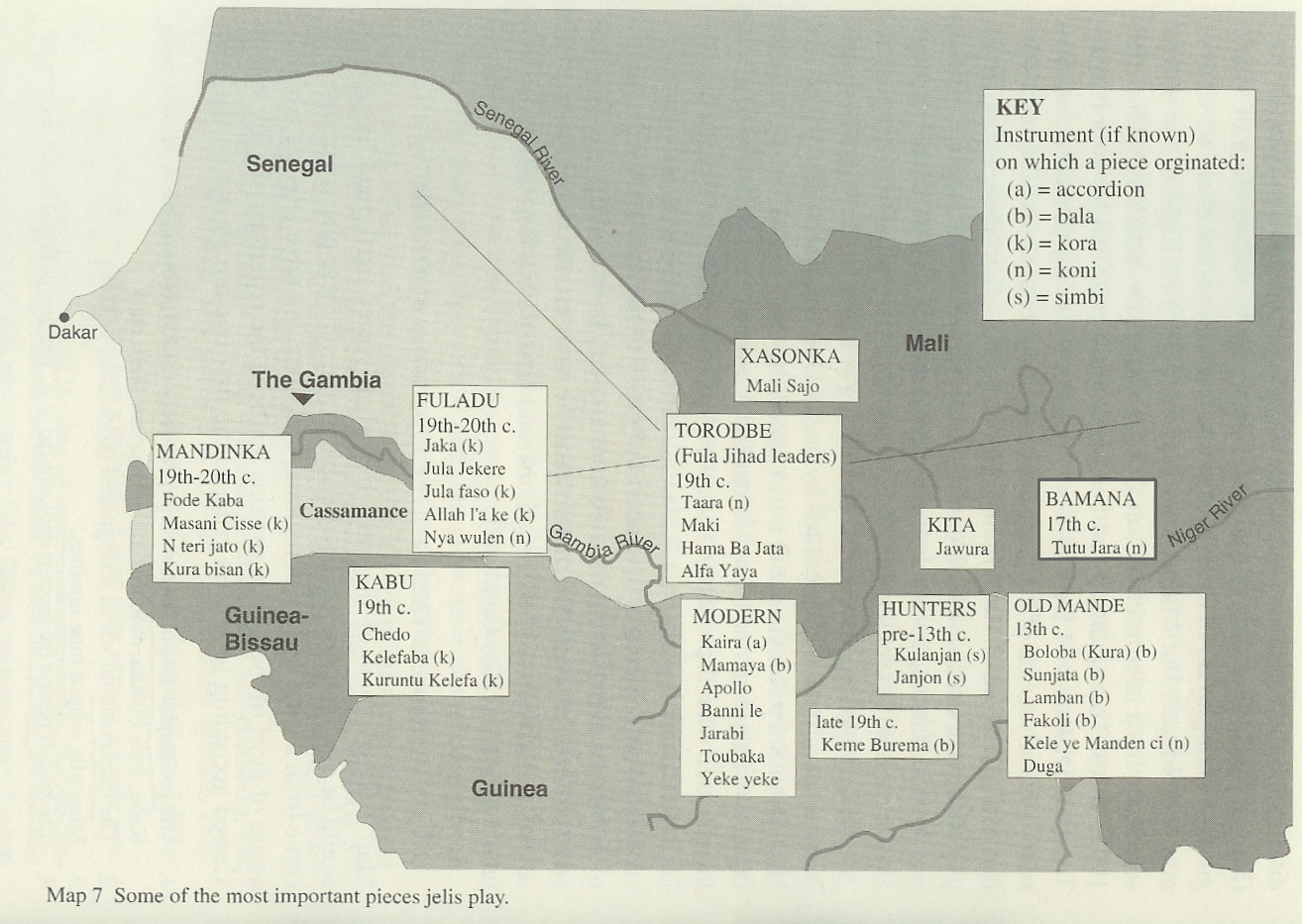

Table One . . . includes the best known, most often heard, or otherwise significant songs in the [Gambian] repertoire. In each column the top few songs are the oldest, and the bottom few are the youngest. The majority in each case fall somewhere in between (often in the nineteenth century), but no chronological ordering beyond this is intended, since it is often not possible to date a song exactly. Most of the songs bear the name of their owner as the title. Where they do not, his name is shown in parentheses next to the title. The letter code at the right represents the person's "claim to fame" or calling in life, as shown in the bottom of the list.

p. 40

Table Two shows the same fifty songs again, grouped this time by the ethnic background of the people commemorated.

p. 44

Musa Mollo himself, as with El Hadj Omar, appears not to have his own song, except for Nya Wuleng ("Red Eyes," symbolizing bravery), which has no text. However, it is very common for the jalis in the eastern regions of The Gambia to sing about him through most of a performance of Sunjata, Kura, or Tutu Jara, since his achievements have a more immediate appeal to present day audiences. A text that is frequently sung calls him the "great bar of soap," as valuable to the people as a bar of soap is to the women washing clothes

Konte, Bai. 1982. Konte Family Mandinka Music: Kora Music and Songs from The Gambia. Virgin, VX 1006.

(Tutu Jara)

Tutu Jara is one of the oldest tunes in Bai's repertoire, being at least 200 years old. His preference for this piece reflects his background, since it is originally from Mali, where it used to be played on a small plucked lute. Tutu Jara is in the same tuning as Dalua. The story goes that a Queen of Mali, whose children never survived infancy, prayed to a snake (called Tutu in Mandinka) to let her next child live. When her prayer was answered and her baby son thrived, she named him after the snake, Tutu Jara. Bai plays two different versions here, the first being the one currently played by the Gambian musicians, and the second (introduced about half way through) being an older version taught him by his father.

Coolen, Michael T. 1983. "The Wolof Xalam Tradition of the Senegambia." Ethnomusicology 27 (3): 477-498.

(Tutu Jara)

p. 489

The largest proportion of traditional songs deals with the history and exploits of major leaders and warriors, such as Sunjata, founder of the Mali empire, and Alfa Yaya, the famous Fulbé warrior. Other songs deal with lesser-known historical figures. One such song is Tutu Jara, a story involving a king named Mansa Damanson, whose wife was unable to conceive children.

p. 490

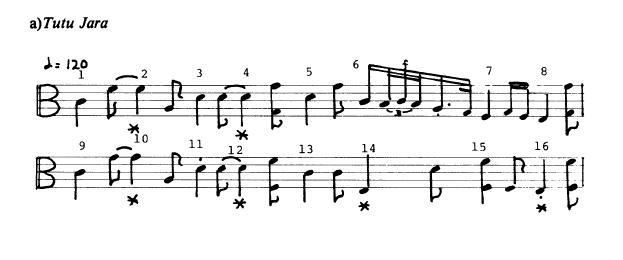

Example 4 illustrates . . . bi-partite fodets with 16-beat patterns. The fodet for the song Tutu Jara subdivides the beats in triple fashion.

Jessup, Lynne. 1983. The Mandinka Balafon: An Introduction with Notation for Teaching. La Mesa, Calif.: Xylo.

(Tutu Jara)

pp. 146–59 (Appendix 2: Balafon Repertoire)

| Title | Tutu Jara |

| Translation: | Tutu - night adder |

| Dedication: | Bambara king of Segou, orig. for Sunjata |

| Notes: | |

| Calling in Life: | king or leader |

| Original Instrument: | Kontingo |

| Region of Origin: | Tilibo |

| Date of Origin: | M (19th & 20th c. up to WWII) |

| Sources: | 3 (R. Knight 1973) |

Diabate, Sidiki. 1987. Sidiki Diabate and Ensemble: Ba togoma. Rogue, FMS/NSA 001.

(Alou waye)

The accompaniment to this song is one of the most classic of Malian tunes, Tutu Jara (Toutou Diarra), named after a king of Segou. There are many versions of Tutu Jara, which is probably several hundred years old; two are featured here. Mariama pays homage to her patrons, such as Babakari Konte, a Gambian trader, and Cheikh Oumar Bathily, a famous merchant from Mali. She also sings standard proverbs, such as 'however good a person is, there is always someone who will talk against him behind his back.'

Kouyate, (El Hadj) Djeli Sory. 1992. Guinée: Anthologie du balafon mandingue. Vol 2. Buda, 92534-2.

(Toutou Diarra)

A very old court tune that praises the "lion king."

Kouyate, M'Bady, and Diaryatou Kouyate. 1996. Guinée: Kora et chant du N'Gabu, Vol 1. Buda, 92692-2.

(Toutout Diarra)

An ancient court melody singing the praise of the "lion king".

Kouyaté, Sory Kandia. 1999. L'épopée du Mandingue. Mélodie, 38205-2. Re-issue of 1973, SLP 36, SLP 37 and "Toutou diarra" from SLP 38.

(Toutou Diarra)

Vieille chanson de geste du Mandingue dédiée à Toutou Diarra, le grand roi bambara de la dynastie des Diarra. Signalons que Diarra signifie en mandeka, lion. Ici, Diarra est aussi bien nom de famille que patronyme de guerre. Cette chanson est l'un des tout premiers succès de Kouyaté Sory Kandia, à ses débuts aux "ballets africains".

Charry, Eric. 2000. Mande Music: Traditional and Modern Music of the Maninka and Mandinka of Western Africa. Chicago; London: University of Chicago Press.

(Tutu Jara)

pp. 146–47

Instrumental recordings of jelis without vocalists are not common, but the number is growing. . . . well-known examples of instrumental music are the solo koni and duo kora renditions of Sunjata and Tutu Jara, respectively, that precede the news broadcasts on Radio Mali several times daily, and the solo kora rendition of Jula faso that is the signature tune for Radio Gambia.

p. 148

pp. 153–54

The koni is a wellspring for jelis of the sahel and northern savanna. The two most important and widespread koni pieces are Tutu Jara and Taara. Tutu Jara, also called Ba juru (Mother’s tune), dedicated to a Bamana king of the Jara (Diara) lineage, tells the story of a barren mother who sought help from a snake (Bm: tutu). With the aid of the snake she bore a child who would become a king of the Jara dynasty, and she named him Tutu Jara. The piece is one of the most popular musical accompaniments used in Mali by jelimusolu to create new praise songs for their patrons, and it is a major piece in the repertory of Malian guitarists, with countless variations.86

86. My Xasonka koni teacher knew a large number of ways to play Tutu Jara—he often cited seventeen versions—and were it not for my impatience and a curiosity to see what other pieces existed, all our lessons would have been spent on Tutu Jara. Indeed, a koni class that I observed at the conservatory in Dakar, taught by respected koni player Numukumba Kouyate, played Tutu Jara exclusively for months. Moriba Koita's (1987-disc) recording of Tutu Jara (called Badiourou) goes through several of the variations.

pp. 162–64

(See Charry, 2000.) (Discussion of koni tunings.)

Tutu Jara kumben, then, refers to the tuning used to play the piece Tutu Jara.

p. 177

Also, koni pieces from Mali such as Tutu Jara are often played slow and allow for more varied kinds of solo melodic playing.

p. 189

In the tuning for Tutu Jara (see above) the range of available pitches is one octave (F to F’) with an occasional drop to the E below of the G’ above (the open fifth string).

pp. 190–92

(See Charry, 2000.) (Koni transcription and discussion.)

Transcription 18 shows two renditions each of two ways of playing Tutu Jara, one of the most important pieces in the Xasonka and Maninka repertories. . . .

There are a few other widely played versions of Tutu Jara and many more that Moussa Kouyate plays, but the two shown in transcription 18 are probably the most common. In contrast to the bala and kora pieces, some of the versions of Tutu Jara are so different from each other that it may be futile to search for an underlying musical model. Tutu Jara might better be considered a collection of pieces, some closely related and others not.

The number of beats per cycle in Tutu Jara is greater than in most other pieces. Dividing the sixteen-beat cycle into four measures of four beats each, a contour emerges.

p. 285

In Guinea, Sunjata, Tutu Jara, and Lamban hardly figure in the modern orchestra repertoires.

p. 290

In F tuning (transcription 27, Taara 2) the bass E string is tuned up to F and the B string up to C. This may be the most popular tuning among present-day Malian guitarists. F major mode pieces that exploit the natural fourth degree (B-flat), such as Lamban and Taara, as well as F Lydian mode pieces exploiting the sharp fourth degree (B), such as Tutu Jara, may be played in F tuning.48

p. 298

57. To date, the clearest and best-recorded example of an ngoni (koni) duo is Moriba Koita's (1997-disc) extraordinary Badiourou (Tutu Jara).

pp. 298–99

(See Charry, 2000.) (Guitar transcription and discussion.)

p. 321

"This is the Sauta tuning [kumbengo]. I just played the piece [julo] Sauta. This here is its tuning [kumbengo]. You can play Tutu [Jara] in it, you can play Allah l'a ke in it. No matter what the piece, if it pleases you, you can play it there [in the Sauta tuning]." (Jobarteh 1990-per:A51)

pp. 398–401 (Appendix C: Recordings of Traditional and Modern Pieces in Mande Repertories)

Koni: Tutu Jara

Unidentified (Guinea Compilations 1962a)

Fanta Damba (1971)

Sidiki Diabate and Batrou Sekou Kouyate (Ministry of Information of Mali 1971,

vol. 5)

Sory Kandia Kouyate ([1973] 1990)

Bah-Sadio

Ami Koita (Bambougoudji, 199?; Den Te Sanna, n.d.)

Tata Bambo Kouyate (Mama Batchily, Goundo Tandja, Amadou Traore, 1985; Nene Sow, 1988)

Walde Damba (Djeli Diourou, Toto, 1989a)

Maa Hawa Kouyate (n.d.b.)

Sunjul Cissoko (1992)

Diaba Koita (mislabeled as Kulanjan, 199?)

Mariam Kouyate, Mamadou Diabate, and Sidiki Diabate (Moussa Diakite, Aladji Sata, 1995b)

M'Bady Kouyate (1996, vol. 1)

Moriba Koita (Badiourou, 1997)

Bangoura, Mohamed "Bangouraké." 2006. Mandeng Jeli.

(Tutuyarah)

From the Mandeng region.

This is a very old traditional Mandeng rhythm. Kelentan Cisoko on kora dedicates this song to BangouraKe. It is the culture of the West African griot to sing the praises of other griots.

Camara, Naby. 2007. Lagni-Sussu Kanteli.

(Toutou Diarra)

A royal melody to praise the Lion King of the Mande empire.

Durán, Lucy. 2007. "Ngaraya: Women and Musical Mastery in Mali." Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London 70 (3): 569–602.

(Bajuru)

p. 589

Throughout the 1970s Batourou Sekou was the regular accompanist to the singer Fanta Damba cini. . . . I asked Batourou Sekou about their distinctive version of Bajuru (also known as Tutu Jara), a version which reputedly "drove people mad" and which created a whole new style of performance in Bamako from the 1970s.

I used to listen to two kora players in Kita, when they played this piece I went crazy ... my Tutu Jara is just how Fanta Damba sings it. Tutu, Lamban, Sunjata and Janjon, those are the most important tunes. People can play Janjon until the morning. Some women sing it until they're blind. Ngaraya kills you slowly.

p. 596

The centrepiece of the recording was performed to the accompaniment of Bajuru. This melody has been one of the favourite pieces in the sumu repertoire of Bamako since at least the 1970s in a version supposedly created by the kora player Batourou Sekou Kouyate and Fanta Damba cini (as discussed earlier). That day, the musicians started to play the Batourou Sekou way, but Kandia stopped them. "No no, not like that. Take it the old way, the Segou way, like this", and she snapped her fingers to indicate a very slow underlying pulse.

Durán, Lucy. 2013. "Poyi! Bamana Jeli Music, Mali, and the Blues." Journal of African Cultural Studies 25 (2): 211-246.

(Bajuru/Bajourou [Tutu Jara/Toutou Diarra])

p. 225

'Bajuru' (or bajourou, using the French spelling), is one of the few heptatonic tunes in the Bamana repertoire, and virtually the only one that is also played by Maninka, Mandinka and Wolof griots,28 where it is better known by the name 'Tutu Jara' (or 'Toutou Diarra'). According to oral traditions in Senegambia and western Mali, 'Tutu Jara' originated in Segu, but it has either been Maninka-ized in its melodic features, or else, as some oral traditions suggest, it originated in the Mande heartland, but was 'captured' by the Bamana.29