dunumba

Keita, Mamady. 1989. Wassolon. Fonti Musicali, FMD 581159.

(Dunumba)

Provient de hamana (région de Kurussa). Ici, les dunun sont toujours joués à trois: kenkeni, sangban, dununba. C'est ce dernier qui mène, tandis que le djembe accompagne. L'importance de l'équilibre entre les dunun est ici fondamentale. Il y a plus de cinquante rythmes de cette famille, dont les variations jouent sur la longeur des phrases et des cycles de mesures. Celui de cet enregistrement a un cycle de deux mesures. A l'origine danse guerrière dans laquelle les garçons des différentes classes d'âge s'affrontaient à coup de nerf de boeuf, on l'appelait "danse des hommes forts". On la pratique aujourd'hui, plus pacifiquement, dans toutes les occasions des fêtes, et mêmes les femmes y prennent part.

Konate, Famoudou. 1991. Rhythmen der Malinke. Staatliche Museen zu Berlin.

(Dununba)

pp. 66-70

Dununba, «la danse des hommes forts», est une très vieille danse qui n'est dansèe, comme son nom l'indique que par des hommes. Il existe environ 20 rythmes dununba differents avec leur danse correspondante. Cette catégorie de rythmes n'existait originairement que chez les Malinkés-Hamanas. Le dununba est devenu cependant très populaire et se joue aujourd'hui également dans d'autres groupes (par ex. Sussu/Guinée; Wolof/Sénégal), même parfois d'une maniere très fortement modifièe. Les differents rythmes dununba ont des éléments stylistiques en commun: Ie tempo consiste généralement en un rythme légèrement plus lent de 12 pulsations. Le tambour kenkeni joue en permanence le même accompagnement. Les formules rythmiques du soliste se ressemblent, mais doivent pourtant être coordonnées aux différentes longueurs des cylces [sic] (les cycles peuvent atteindre 8 x 12 pulsations) et aux pas des danseurs. Avant le début d'une fête dununba, les batteurs se retrouvent devant la maison du soliste (djembéfola). Pour annoncer la fête, ils jouent pendant un petit moment le ryhtme [sic] dununbè (enregistrement [12]). Après une courte pause la musique reprend. Ceci indique aux jeunes filles encore célibataires de se rendre sur la place de danse du village (barra) afin d'accompagner les tambours de leurs chants et battements de main. Pendant que les batteurs entament le rythme pour la troisième fois, ils se dirigent vers la place de danse. Une fois arrivés ils allument un petit feu et s'en servent pour tendre les peaux des instruments. Les jeunes filles, qui ne se sont jusqu'à ce moment là pas encore présentées sur la place, seront punies de cinq légers coups de fouet sur les jambes.

Entre temps les barratis s'y sont déjà rendus; ils forment un groupe de 30 à 40 hommes grands et forts qui déterminent et surveil lent tout le déroulement de la fête. Comme maîtres de la place de danse, ils sont en possession des instruments et détiennent le privilège de la première danse. Le titre de barrati ne peut se transmettre qu'à l'intérieur d'une même famille. Si d'autres hommes dësirent devenir les nouveaux barratis, ils doivent lors d'une fête dununba se réunir en un groupe fermé et avancer contre les barratis. A cela suit un dur combat mené avec des fouets en peau d'hippopotame; si les provocateurs gagnent, ils deviennent alors les nouveaux barratis. Lorsque la musique retentit à nouveau, les barratis engagent alors la danse en se plaçant sur deux rangs (voir schéma). Chaque danseur tient dans sa main droite une hachette décorée avec art (gende) et dans sa main gauche un foueten peau d'hippopotame (manimfosson).

Les deux rangs se dirigent alors lentement sur le même pas de danse vers les joeurs de tambour. Une fois arrivé, chaque barrati termine la danse séparément avec un solo. C'est à ce moment là que les hommes donnent le meilleur d'eux-même, voulant par là impressionner les jeunes filles qui se tiennent derrière les batteurs. Par la suite d'autres hommes peuvent également demander aux barratis la permission de danser.

Durant toute la fête un homme à l'apparence étrange, habillé d'une peau de singe, danse tout autour de la place.

Après le rythme dununbè suivent d'autres rythmes de la catégorie dununba avec une chorégraphie identique. (par ex. bandogialli [13], bolokonodo [14], takosaba [16]).

La danse dununba s'exécute pour toutes les grandes fêtes.

Kaba, Mamadi. 1995. Anthologie de chants mandingues (Côte d'Ivoire, Guinée, Mali). Paris: Harmattan.

(Dounounba)

p. 7-8

Parmi les chants mandingues reconnaissable par leur rythme, on peut citer entre autres : . . . les dounounba au rythme trépidant dansés surtout par les hommes pour lesquels c'est l'occasion d'exhiber leur musculature et d'afficher leur excellent condition physique.

Les femmes, par des battements de mains et par leur chants, les encouragent ou les accompagnent dans leurs danses au milieu d'un grand cercle d'enfants et de spectateurs qui participent. Quand il fait nuit, les danseurs portent des flambeaux de paille qui illuminent la place publique. Parfois, dans leurs chants, les femmes citent les noms des danseurs les plus talentueux. Quand les danses se font avec mouvements d'ensemble, elles offrent un spectacle fascinant qui enveloppe les nuits malinké de Kouroussa, de Baro, de Siguiri, de Kankan et d'ailleurs ; . . . En dépit de l'origine animiste des dounouba et des soly, ces danses sont pratiqué es de nos jours même dans les familles les plus islamisées qui s'y étaient d'abord opposées avant de les adopter.

p. 72

QUAND JE T'APPELLE BILAKORO1

(M'BAFO BlLAKORO)

Quand je t'appelle bilakoro,

C'est-à-dire incirconcis,

Ce n'est pas pour t'injurier.

Quand je t'appelle bilakoro,

Ce n'est pas pour t'humilier,

Ce n'est pas pour t'insulter,

Ce n'est pas pour te gronder,

Mais, c'est que j'aime te regarder

Danser le rythme de dounouba,

La danse des hommes forts !

Oh, gros bilakoro !

Oh, Dala Sandala,

Tu es un grand danseur !

Et c'est pour rendre

Hommage à ton courage

Que la femme s'élance

Dans le rythme trépidant

De cette fameuse danse

Endiablée des hommes forts.

1 A l'époque préislamique, la circoncision se faisait assez tard, au seuil de l'âge adulte. C'est aussi à cet âge que, plein d'énergie et de force, le jeune à circoncire était le mieux apte à danser le dounouba (tam-tam), la danse mandingue des hommes forts. Et à l'occasion de ces danses, les femmes font l'apologie de ces danseurs intrépides que sont ces jeunes incirconcis qui font aussi l'admiration des spectateurs. C'est aussi l'occasion pour ces bilakoro de faire étalage de leur force, de leur habileté et de leur puissante musculature.

Le Dounouba, c'est le nom du tam-tam trépidant qui appelle à la danse les hommes valides et les femmes une fois la nuit tombée. C'est aussi le nom de la danse endiablée pratiquée surtout par les hommes au torse nu, aux biceps gonflés à la lumière des centaines de torches éclairant la place du village. En pays malinké, la nuit, c'est un régal pour les yeux et les oreilles que ce spectacle de mille flammes illuminant la place publique.

p. 75

PLUIE MATINALE1

(SOMA SANDJI)

C'est une pluie très matinale

Qui tombe maintenant à torrents

Au moment où j'entends le chant

D'un oiseau de soleil couchant !

Quel est ce petit oiseau au long cou

Qui m'appelle près de la rivière ?

Frère Sono, entends-tu parailleurs

Le crépitement du tam-tam

Sur la place du village ?

Or la pluie continue de tomber.

Restons donc ensemble ici àl'abri,

Ne nous laissons pas inutilement

Mouiller par la pluie du matin

Qui frappe tout le monde

Et n'épargne personne !

1 La pluie matinale mouille tous ceux qui osent la défier. Aüssi, ceux qui lancent le défi se font souvent appeler "pluie matinale" parce que si vous les affrontez, ils vous frappent sans pitié. La pluie du matin n'épargne sur tout pas le paysan en route pour le champ.

C'est aussi un autre chant de dounouba, c'est-à-dire de danse trépidante la nuit comme le chant précédent dénommé "M'bafo Bilakoro".

p. 80

MES CHERS PÈRE ET MÈRE1

(NANI N'FALOU)

Ah, mes chers père et mère !

Aujourd'hui, grande est ma joie

De partir ce jour à la chasse

En compagnie du grand chasseur

Pour qu'il veuille bien me procurer

Du bongibier qu'il va capturer

Toi, l'homme aux yeux très rouges,

Je t'accompagnerai aujourd'hui

A la chasse en pleine brousse.

Je ne m'adresse, ni au faux chasseur

Qu'est le chasseur de simple grillon,

Et ni au faux chasseur poltron

Qu'est le chasseur de charognard !

Mais à toi, l'homme aux yeux rouges

Que j'accompagnerai aujourd'hui

A la chasse en pleine brousse !

Ah, mes chers père et mère,

Aujourd'hui, grande est ma joie

De partir en brousse à la chasse.

1 Les jeunes sont heureux d'accompagner les grands chasseurs à la chasse. Les chasseurs expérimentés ont souvent les yeux rougis par le soleil et par l'attention soutenue toujours aux aguets. Un grand chasseur ne peut ramener de la chasse ni un vautour ni un grillon qui sont trop faciles à atteindre. Ce chant suit le rythme du dounouba.

pp. 94-5

L'HOMME VAILLANT1

(BELE BELE)

L'homme viril et vaillant

Peut passer tout son temps

Sur n'importe quelle terre.

Il se tirera toujours d'affaire

Grâce à la vaillance

Que lui a léguée sa mère.

Si le jeune adolescent

De vient un menteur,

Sa mère en est responsable.

S'il de vient un voleur,

Sa mère en est responsable.

Si tu es un homme vaillant,

C'est toujours grâce à ta mère,

Qui ne sait pas parler aux hommes

Qui ne plaisante pas avec les hommes

En faisant du libertinage

Et tu porteras sur toi l'empreinte

De cette excellente conduite.

Car certaines décisions du mari

Ne doivent pas être contestées

Par la femme, mère de famille.

Les enfants trop douillets

Deviennent tous des hommes

Sans coeur et sans courage,

Qui n'atteignent pas leurs objectifs.

Car si la massue lancée n'atteint pas

Le volumineux fruit sec du baobab,

Elle ne pourra même pas effleurer

La mince tige qui porte ce fruit

Et elle retombera bredouille sur terre1.

1 Cet hymne à la mère est un chant à la gloire de toutes les mères. Ce chant est aussi ancien que le matriarcat au Manding, bien avant l'avènement de l'Islam. Il est reconnu que l'expression "M'ba" qui signifie "ma mère" prend sa racine à cette époque où la réussite de tout homme était considérée comme résultant de la bénédiction de la mère, Et quant on posait la question "Comment ça va?" à quel qu'un, il répondait couramment : Ça va grâce à ma mère". Puis cette réponse a été abrégée pour donner seulement le mot "ma mère" ou en mandingue "M'ba", C'est pourquoi, de nos jours encore, ce mot "M'ba" est la réponse à la question comment ça va? Ça va bien? Et l'intéressé répond "M'ba" qui signifie "ma mère" ou bien "grâce à ma mère" ou bien encore, "ça va grâce à mère". Ce "M'ba" n'est pas une déformation de "marhaba" qui est un mot arabe. Il remonte à l'époque préislamique matriarcale. La valeur de la mère a été atténuée par l'islam, sans pour autant disparaître : Samory n'a-t-il pas accepté de se constituer prisonnier et esclave pour racheter sa mère ?

Le présent hymne qui remonte à la nuit des temps constitue avec les chants de circoncision, d'excision, de mariage et de danse, un véritable code de la famille mandingue préislamique.

C'est un chant de dounouba, ce tam-tam trépidant au cours duquel les hommes au torse nu viennent en faisant étalage non seulement de leur talent de bon danseur mais aussi de leur condition physique athlétique.

p. 125

LE PARDON1

TOLAYE

Je te pardonne

Pour l'amour de Dieu

Et des on prophète.

Je te pardonne

Pour l'amour du Seigneur,

Rigoureux arracheur d'âmes.

Je te pardonne

Pour l'amour de Dieu

Et de son prophète.

Je te pardonne

Pour l'amour du Seigneur,

Casseur du cou des hommes.

Je te pardonne

Pour l'amour de Dieu

Et de son prophète.

Je te pardonne

Pour l'amour du Seigneur,

Tueur de tous les hommes.

1 C'est un chant de dounouba qui suit un rythme préislamique puissant, violent, envoûtant alors que le contenu est islamique. C'est donc un morceau composé par des animistes mandingues nouvellement convertis à l'islam et qui ont conservé la forme préislamique dans le rythme. Cette forme violente envoûtante se retrouve aussi dans les mots et expressions qui émaillent le chant.

Ce morceau est joué avec le tam-tam au rythme trépidant sur la place publique. Les danseurs, des athlètes au torse nu, exhibent leur musculature et remuent leurs bras dans des gestes saccadés avec des mouvements d'ensemble alors que les femmes chantent. Vers 1938, j'aimais voir ces hommes danser en tenant des torches de paille qui illuminaient la place publique.

p. 141

MON FILS SANASSI1

(N'DENKE SANASSI)

Sanassi, mon cher enfant !

Quelle complication ?

A la circoncision

De leurs chers enfants,

Les riches mamans

Et les bons papas

Des fils à papa

Tuent des moutons

Pour leurs enfants !

Moi, sans mouton

Et sans argent,

Je n'ai rien à te donner

Pour ta circoncision

Et dans ces conditions

En bon croyant très pieux,

Je m'en remets à Dieu.

1 Ce morceau est la complainte d'un père pauvre qui ne peut s'acquitter des devoirs qui lui sont dévolus à l'occasion de la circoncision de son enfant. Sa seule consolation, c'est de pouvoir s'enremettre dans ces conditions a Dieu.

C'est le chant improvisé par le père d'un de mes compagnons de circoncision qui se nommait Sanassi. Le père de Sanassi était consterné en constatant que les parents des circoncis faisaient des offrandes que lui était incapable de faire pour son fils. Ce chant emprunte le rythme trépidant du dounouba.

p. 189

MON ARGENT1

(N'NAWODI)

Eh ! Donne-moi monargent [sic]

Monargent !

Donne-moi monargent

Monargent !

Il comprend précisément

De pauvres pièces de unsou [sic]

Monargent !

Donne-moi monargent

Monargent !

Il comprend précisément

De pauvres pièces de dix centimes

Monargent !

Donne-moi monargent

Monargent !

Il comprend précisément

De pauvres pièces de vingt-cinq centimes

Monargent !

Donne-moi monargent

Monargent !

Il comprend précisément

De pauvres pièces de cinquante centimes

Monargent !

Alors, donne-moi monargent.

1 Il s'agit là de l'énumération des pièces de monnaie métallique, de bronze et d'étain en circulation en 1939 en Afrique Noire francophone. Ces pièces comprenaient :

- celles de 1 sou ou 5 centimes

- celles de 1 koporo ou 10 centimes

- celles de 1 pikini ou 25 centimes

- et en fin celle de 1 tanka ou 50 centimes.

C'est un chant de dounouba de Kankan qui se chante à une seule voix sauf les mots "Mon argent" qui sont repris en choeur.

Charry, Eric. 1996. "A Guide to the Jembe." Percussive Notes 34 (2): 66-72.

(Dundunba)

p. 68

Jembe repertories draw from many different sources. There are widespread core Maninka rhythms and dances such as Dundunba (one of the most widely recorded jembe rhythms), as well as more geographically limited dances such as Soli (Maninka of Guinea), Dansa (Xasonke of Mali) and Sunu (Bamana of Mali).

Some rhythms honor groups of people, such as Jeli don (jelis), Woloso don (a class of slaves) or Dundunba (strong or brave men). (In Maninka, "don" means "dance.")

Over thirty named songs and dances are listed on the [Les Ballets Africains (1991)] CD liner notes for a performance lasting just under one hour. Some pieces are played for less than one minute, while others, such as Dundunba, are played for almost ten minutes, reaffirming their importance.

Blanc, Serge. 1997. African Percussion: The Djembe. Paris: Percudanse Association.

(Dununba)

From the Maninka ethnic group, originating in the Hamana, in the Kouroussa region of Upper Guinea.

The dununba is also called "the dance of the Strong Men". Key instruments, the dunun follow the dance while the djembe accompanies it. that is why the rhythm is named after the dunun.

It is a very acrobatic dance. The dancers, called Barati1, use it to show the betrothed and the important people of the village their vitality and bravery.

Turning in front of the assembly, they strike their while performing risky somersaults and jumps. In some regions this dance is practised more "peaceably". Women participate with their own specific movements.

There are many variants of the dununba rhythm.

1. Barati = master of the Bara. The bara is the public place where the dunumba is danced.

Billmeier, Uschi. 1999. Mamady Keita: A Life For the Djembe—Traditional Rhythms of the Malinke. Engerda, Germany: Arun-Verlag.

(Dununba)

"Dance of the Strong Men."

Dununba is the name of a family of rhythms consisting of approximately twenty to thirty traditional Malinke rhythms.

They all have in common the meaning of the dance, which was originally only danced by the men. With this dance, the men settled a tough, and sometimes even violent and bloody, fight to determine the superiority between different age groups in the village.

Even today, the social life of adolescents and young adults is mostly determined by belonging to different age groups. Each group has a leader, takes over specific tasks and duties, and enjoys certain rights.

The group of the older ones, called baratigi (approximately 20 to 25 years old), enjoys in comparison to the younger ones, called baramakono (approximately 15 to 20 years old), more rights and more freedom to make decisions. Sooner or later, the younger people want to excape the patronizing of the older ones and take their place. This is communicated to the leader of the baratigi though the symbolic gift of 10 cola nuts.

For this dispute between the different age groups, a Dununba celebration is organized. In the past, these were major festivities, with the whole village taking part.

The dancers wore headbands and large trousers. In one hand, each held an ax (gende), and, in the other hand, a whip made from the leather of a hippopotamus (manimfosson).

At the beginning of the festival, either the rhythms Dunungbe or Gbada were played, then the two groups passed by one another and formed two circles.

Finally, the men faced each other in two rows, and the fight would begin.

The rows of men beat each other, in turn, with the whips until one of the groups surrendered. In the past, these fights were fought until the bloody end. Today, it is limited to a playful version, without a real fight, or just to a suggestion of a fight.

The Dununba rhythms have the following musical elements in common: the tempo is andante; and the kenkeni always plays the same pattern.

Musically speaking, the dununba and sangban play the most important parts, and the phrase of the dununba can be rather long. There are many variations and different forms of "heating up the rhythm" (échauffements) for each of the individual rhythms. Not all Dununba rhythms are fight dances. Today, Dununba is a popular rhythm and very much favored all over Guinea. In a modified versions [sic], Dununba is also played in other West African countries.

The dunun are played very diversely in these rhythms.

Forè Foté. 1999. Wonberé: Music and Dance in Black and White.

(Doundoumba)

The doundoumba family of rhythms originate among the Malinké of Hamanah, a region near Kouroussa in eastern Guinée, and are generically referred to as the, "Dance of the strong men." Three different doundoumbas are interconnected in this arrangement in their most traditional form utilizing only the dunun ensemble. The kenkeni provides the link in the doundoumba family repeating a short rhythmic cell, while the sangban establishes the length and cycle of the phrase for the Dunumba to create its improvisations.

Koumbassa, Youssouf. 1999. Wongai: Let's Go! Vol. 2. New York, NY: B-rave Studio/Youssouf Koumbassa.

(Doundounba)

This dance is called Doundounba. Doundounba is coming from the village Kouroussa. We have a different music from doundounba. There's more than fifteen different music from doundounba; it's all have different name. Today doundounba I'm going to use today is called Konde. Doundounba is for strong dance from Guinea. *

* Transcription mine.

Polak, Rainer, prod. 1999. Jakite, Dunbia, Kuyate, and Samake: Bamakò Fòli: Jenbe Music from Bamako (Mali). Self-produced.

(Dununba)

This is how Dununba is played in Bamako. They sometimes call it Lagineka (La-Guinée-ka) Dununba, i.e. "the Dununba of the people from Guinea". It is played primarily in the ballets, but only to a lesser extent in the festivals. When some troupe members or professional dancers perform at a festival, they definitely will show off their skills with it, setting themselves off from the amateur dancers.

Zanetti, Vincent. 1999. "Les maîtres du jembe: Entretiens avec Fadouba Oularé, Famoudou Konaté, Mamady Keïta et Soungalo Coulibaly." Cahiers de musiques traditionnelles 12: 175-195.

(Dunumba)

pp. 179-80

4. . . . Dans le discours de Famoudou et de Fadouba, il recouvre également une famille de rythmes et une danse maninka spécifique, également appelée dunumba («le gros tambour de basse»), par laquelle les hommes manifestent leur force et leur courage. Très populaire en Haute-Guinée, dans les régions de Kankan, Siguiri et Kouroussa, cette «danse des nommes forts» peut être tout à la fois un rituel de passage d'une classe d'âge à une autre pour les jeunes gens, un divertissement pour toute la communauté et un mode de régulation de la société en cas de conflits personnels. Lors du concert des «Maîtres du djembé», le rythme du dunumba a provoqué une très forte réaction d'enthousiasme auprès des nombreux danseurs masculins qui étaient dans le public.

p. 181

Nous, on connaît le fond, on sait pourquoi et à quelle occasion on joue tel rythme : . . . dans le Hamanah, autour de Kouroussa, les rythmes de dunumba. Le Hamanah, c'est le pays d'origine de Famoudou Konaté, et pour moi, Fadouba Oularé, c'est à Faranah. Mais moi aussi, j'ai passé tout mon temps à Kouroussa depuis l'âge de 12 ans. C'est pour ça que je connais moi aussi profondément le dunumba. Ma maman vient de Kouroussa.

Charry, Eric. 2000. Mande Music: Traditional and Modern Music of the Maninka and Mandinka of Western Africa. Chicago; London: University of Chicago Press.

(Dundunba)

p. 213

17. . . . Hamana is home to the most widespread jembe piece, Dundunba (see below). In neighboring Muslim communities, such as Kankan, traditionally violent Dundunba dancing has been suppressed.

pp. 218–20

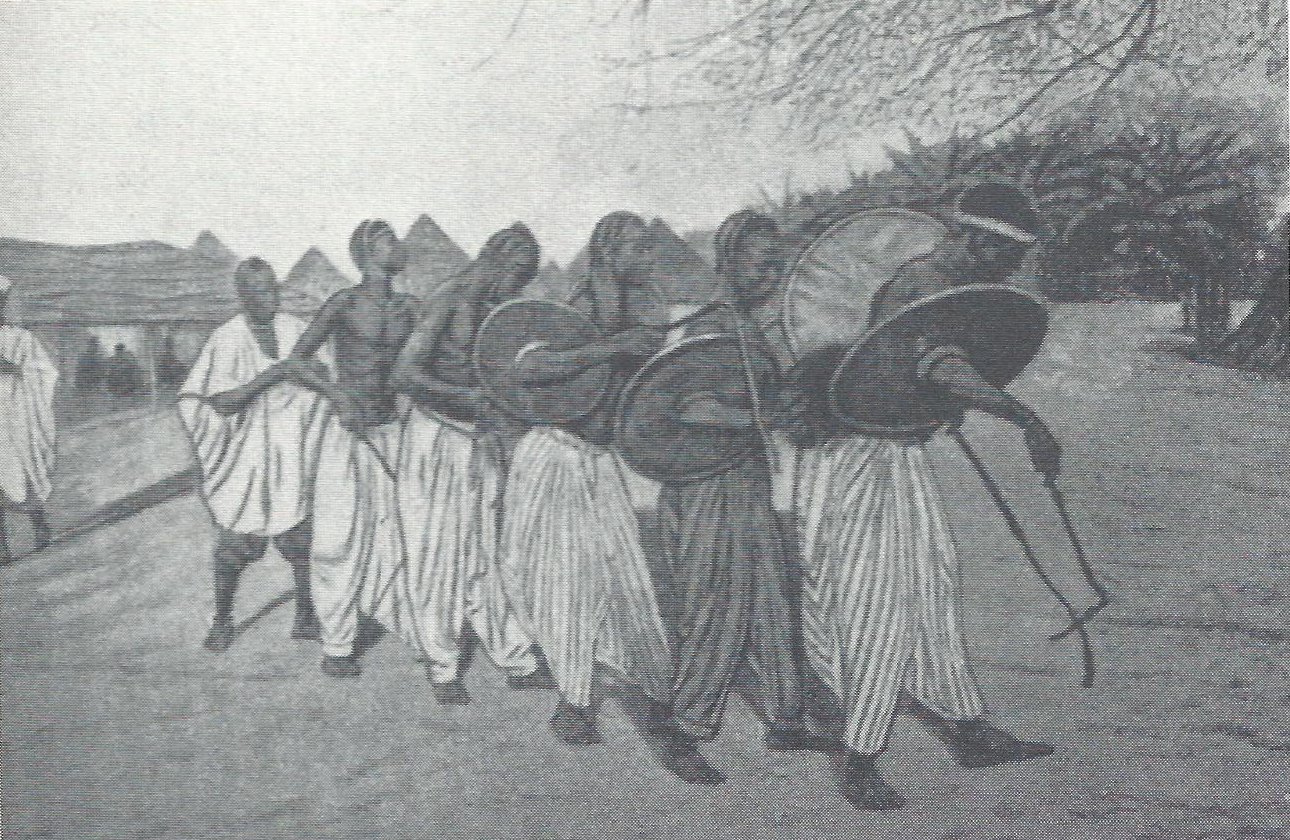

Judging from the number of drummers who have recorded it, the most popular rhythm among jembe drummers by far is Dundunba (Dununba, Dunumba), a collection of related rhythms probably reflecting local variations played in Upper Guinea.22 It is typically described as a dance of strong men bearing whips that they use to strike each other, originating in the Maninka chiefdom of Hamana in the region of Kouroussa in Upper Guinea. Its popularity as a dance spread north to Bamako and south to Conakry, where it entered the repertory of the national ballet troupes. In Conakry nowadays the term dundunba is popularly used for any kind of jembe-based dance celebration. Early documentation of the dance includes a photograph published by Chauvet (1929:152) captioned "un tam-tam à Kouroussa (Guinée)" (plate 27).23 The attire of the dancers is very close to that of the dancers in modern Ballets Africains (1967-vid, 1991-vid, n.d.-vid) performances of the piece.

Plate 27 Dundunba dancers at Kouroussa, Guinea. "Un tam-tam à Kouroussa (Guinée)." Photo by Lieutenant Bacot. From Chauvet (1929:152, fig. 12 bis).

In the early 1960s Claude Meillassoux (1968b:93–96) saw the dance performed in Bamako by migrants from Kouroussa and reported that it was danced regularly on Sundays. What he saw was relatively tame, but his description of how it is danced in Kouroussa vividly portrays its significance. Meillassoux indicates that, traditionally, circumcised males fifteen to twenty-eight years old prove their courage by dancing Dundunba. The dancers tie handkerchiefs around their heads.

In the early 1960s Claude Meillassoux (1968b:93–96) saw the dance performed in Bamako by migrants from Kouroussa and reported that it was danced regularly on Sundays. What he saw was relatively tame, but his description of how it is danced in Kouroussa vividly portrays its sidnificance. Meillassoux indicates that, traditionally, circumcised males fifteen to twenty-eight years old prove their courage by dancing Dundunba. The dancers tie handkerchiefs around their heads.

On both arms magic leather bangles sustain their strength; in one hand they carry a small war ax or a saber, in the other a wene (short whip) made of the plaited membrane of a donkey's penis. They walk in single file around the bara (dance ground), each whipping the man in front of him until the blood runs. Those who cannot bear the pain leave the file amidst the jeers of the crowd. . . . The dunũba formerly was danced only at great occasions, to celebrate a victory or a circumcision. Today, in the bush, the most usual occasion is at circumcision time. (Meillassoux 1968b:94)24

Other descriptions of the dance are given by Sory Camara ([1976] 1992:292) and in the notes to two extraordinary recordings by Famoudou Konate (1991-disc), who plays six Dundunba variations, and Mamady Keita (1996-disc), who, along with guest Famoudou Konate, plays twelve. Konate, lead jembe player with Les Ballets Africains in the early years of independence, comes from Kouroussa, the Dundunba heartland. In Keita's description, similar to Camara's, concentric circles of males are formed in the village dance space (bara) according to their age groups (kare). The barati, members of the oldest youth group, which owns the dance space, are in the center, and when someone from a younger group wants to join them he moves out of his circle and reciprocal whipping takes place with a member of the older group. The younger male is accepted or rejected from the inner circle according to his courage. Konate's description indicates that an outside group collectively challenges the inner circle. In its village context, Dundunba had the status of a serious ritual. But Meillassoux (1968b:96) suggests that, removed from the village, the dance had moved from ceremony to entertainment; the movements were done, but not the whipping—except on certain occasions. Meillassoux (1968b:96) had been told of an independence celebration in 1959 in which Kouroussa natives in Bamako held a Dundunba where "the whipping was very rough." Taking the examples of Dundunba, Komo, and Manjani (see below), it appears that jembe drumming in serious ritual contexts may have declined by the time of independence.

22. The bilabial consonant b in the suffix -ba (big) changes the nasal n to m, yielding the correct pronunciation Dundumba or Dunumba.

23. Another early piece of documentation of Dundunba comes from Joyeux (1924:210), who described what he called a "sect" called Bando (monkey), which consisted of dancers who wore goatskin (formerly monkey skin) collars. The head of the Bando dancers at the time was Diely Koro. Famoudou Konate (1991-disc:66–70) includes Bandogialli (probably named after bando and dieli) as a Dundunba variation. Konate's description of the dance (written by Johannes Beer) conforms with a scene in Les Ballets Africains (1991-vid).

24. Notes by Beer (Famoudou Konate 1991-disc:68) and Flagel (Mamady Keita 1996-disc:13) indicate that the whips are made from hippopotamus skin, manimfosson.

pp. 225–28

(See Charry, 2000.) (Jembe & Dunun transcriptions w. discussion.)

Transcription 20 shows a Malian version of Dundunba, one of the most difficult pieces for non-Africans to perceive rhythmically. Dundunba is immediately identifiable by the accompanying dunun (kenkeni or konkoni) part, three strokes that surround the main beats. Heard in isolation, the first and last of the three strokes can easily be misapprehended as falling on the main beats. But compared with the second jembe accompaniment, it can be seen that the kenkeni part is replicated by the bass and two tone strokes on the offbeats.29

29. When I first learned Dundunba in Bamako, I was having trouble understanding the jembe parts against an accompanying konkoni part that would start first. I asked my teacher how people in a dance circle would clap to this part, and he replied by telling a nearby youngster to clap. Without any further prompting, she immediately did so, placing the claps where they should be, matching the slaps on the jembe pats. The claps also match the dancer's footsteps, called don sen (dance step). Dundunba versions from Guinea often feature a different lead dundun (or sangba) part.

p. 285

Like Jawura in Mali, the jembe and dunun rhythm known as Dundunba can often be heard in arrangements of modern Guinean music.

Kienou, Amadou. 2004. Sya: Rhythmes de la Tradition du Burkina Faso. Felmay, FY8083.

(Doundounba)

Played to accompany the dance of the strong men who meet after the harvest to test each other's strength.

Bangoura, Fode Seydou. 2005. Fakoly 1.

(Takonani et Demosonikelen)

Both Takonani and Demosonikelen are Doundounba dances of strong men. The singers are telling everyone to get together tonight for Doundounba, announcing that the Bamana rhythms are coming out ... the unique sound of ... _uin_e.

Bangoura, Mohamed "Bangouraké." 2006. Mandeng Jeli.

(Doundounbadon)

This rhythm is the strongest dance rhythm in Guinea It is a dance about strength [sic] of men and women competing against each other; the man is trying to dance the woman's steps and the woman trying to dance the man's steps. It is now the most popular rhythm in Conakry and played at many ceremonies.

Benkadi. 2006. Moné Mani. Leo Brooks, LB006.

(Dounounba)

Dounounba is "The Dance of the Strong Men". There are dozens of rhythms in the Dounounba family, all with different dances and circumstances when they are played.

Balan-Sondé

Konate, Famoudou. 1991. Rhythmen der Malinke. Staatliche Museen zu Berlin.

(Balan-Sondé)

Balan-sondé consitute une exception parmi les rythmes dununba. Il est joué lors d'une fête de circoncision pendant laquelle les femmes ont le droit, elles aussi, de danser. Pendant que les hommes se déplacent au pas dununba habituel, les femmes, elles, dansent sur les pas qui correspondent au rythme soli. Balan est un village dans la région de Kouroussa; sondé signifie »voleur«. Les habitants de ce village sont surnommés en plaisantant les voleurs.

Rythme: cycle de 24 pulsations, subdivisé en 2 groupes de 12 pulsations.

Paroles de la chanson:

Vous, habitants de Balan, vous étes des voleurs!

Nous ne sommes pas des voeurs, nous n'avons encore rien volé.

Vous avez menti. Ce n'est pas vrai, pas vrai.

Delbanco, Åge. 2012. West African Rhythms. Charleston, SC: Seven Hawk.

(Balan-Sondé)

From Balan near Kourourssa. A dununba rhythm exceptionally played during circumcision celebration; the men dance dununba steps and the women dance soli steps.

Bando Djei

Konate, Famoudou. 1991. Rhythmen der Malinke. Staatliche Museen zu Berlin.

(Bandogialli)

Bandogialli est le nom d'une certaine espèce de singe dont la queue est blanche. Les danseurs portent pour cette danse un collier, auquel est attachée une touffe blanche symbolisant la queue blanche du singe. Le rapide haussement et abaissement des épaules donne à la touffe un vif mouvement de balancement.

Bandogialli est dansée exclusivement par les barratis.

Rythme: cycle de 24 pulsations, subdivisé en 2 groupes de 12 pulsations (partie).

Paroles de la chanson:

Le bando (danseur du bandogialli) est arrivé.

La pluie ne doit pas l'atteindre.

Mère, père, il danse vraiment bien!

Keita, Mamady. 1995. Mögöbalu. Fonti Musicali, FMD 205.

(Bando Djei)

Dances of the strong men of Hamana (Kouroussa, Upper Guinea) in the Dunumba rhythm. Amidst all the praises addressed to N'na Dödö, the goddess known as Nakouda or Koudaba is now honoured. Worshipped by the people of Hamana, mother Kouda is particularly invoked during the feast of Bölèh pond in Baro, a village situated between Kouroussa and Kankan. This is the occasion to thank her with offerings for wishes granted or to implore her for success in the future.

| N'na Dödö nin né, Bomba la Dödöö. | You, mother Dödö, Dödöö of the great house, |

| N'na Dödö nin né, N'na gbadon Dödööd. | You, mother Dödö, cook, Dödöö, |

| Ina moyi ni lolo lé laa | Your mother gave birth to a star. |

| Baatèmah loloh | A star in the midst of the waters, |

| Djitèmah loloh | A star in the depths of the waves. |

| Ibaa kouma, koulé kouma kodjon | If you speak, they say that you talk too much; |

| Iba imakoun, koulé djanda ni founoukéya Döö | If you are silent, you who are young, they say that you are pretentious. |

| Kouma yé sondja lé dij, | Words become suffering for you |

| Makoun ködö tè lon | But the depths of silence cannot be measured. |

| Kerèn-könöni kassi daa | Kèrèn-Könöni* has sung. |

| N'na konda ééé | O mother Kouda, |

| N'na konda ya naa | let mother Kouda come. |

| Hamana dia daa! | The living is good in Hamana. |

| Noulou nani donkan né ma ééé! | It was for the dancing that we, we came. |

| Sila yèlèni bandan né la ééé! | The path leads to the kapok tree.** |

* a small bird famed for its chattering.

** the kapok tree is often planted in the centre of the bara or space for dancing.

Camio, Mansa. 2006. An Bada Sofoli: Malinké Dunun Music of Upper Guinea. Middle Path Media, MPM 001.

(Bandodjéi)

Bando djéi is a dance inspired by a black monkey with a white tail that is found in upper guinea. During the French colonial times in Guinea taxes were imposed on the people. This song is in remembrance of a time when the people of Gberedou went to the regional capital KanKan and danced Bando for the mayor the "Papa, Red-Commandant." He enjoyed the dance so much that they were pardoned from paying their taxes.

| N'né wara KanKan | We have gone to Kan Kan |

| N'né wara commandant téréyén | We have gone to the commandant's |

| N'fa Commandant-Oulén | Papa, Red-Commandant |

| M'baranan nan dounounba djoulou kö | We have come with the rope of our doundoumba |

| N'né wara KanKan | We have gone to Kan Kan |

| N'né wara commandant téréyén | We have gone to the commandant's |

| N'fa Commandant-Oulén | Papa, Red-Commandant |

| M'baranan nan bando djala kö | We have come with the scarf of our Bando |

| Kiyén to Allayén | Excuse us! In the name of God |

| N'né birito | I pardon you |

| Alla nan kélayén | owing to God and his messenger |

| N'né birito Allayén | I pardon you, because of God |

| N'né birito | I pardon you |

| sangban djoulouyén | because of the rope of the sangbana |

| Hé hé djéi wo | Hé hé djéi wo |

| He hé Bando djéi-dönan | Hé hé the tail of the Bando dances well |

| Hé hé djéi wo | Hé hé djéi wo |

| He hé Bando djéi-dönan | Hé hé the tail of the Bando dances well |

| Hé hé djéi wo | Hé hé djéi wo |

| Hé hé Gberedou sara | Hé hé the popularity of Gberedou |

| Saralani Bando djéila | The tail of the Bando has become popular |

Delbanco, Åge. 2012. West African Rhythms. Charleston, SC: Seven Hawk.

(Bandodjeli)

Dununba rhythm from the region of Kouroussa, Upper Guinea.

Bara Rota Dunun

Delbanco, Åge. 2012. West African Rhythms. Charleston, SC: Seven Hawk.

(Bara Rota Dunun)

Dununba rhythm played in the village to announce that the dununba dance is beginning at the village square (the bara.)

Bolokonondo

Konate, Famoudou. 1988. Famoudou Konaté maître-djembé et l'Ensemble Hamana Dan Ba. Guinée: Percussions et chants malinké, Vol. 2. Buda, 1977832.

(Bolokonondo II)

C'est un nouveau Dunum (danse des hommes forts) crée par Famoudou mais comme son nom l'indique, inspiré par le rythme Bolokonondo original.

| Eh nyewa ködö ambö barawa, ambö barawa nyewa ko dambala koduman | Let's go to the river, my friend has left, it will be good to bath at the river's edge |

Konate, Famoudou. 1991. Rhythmen der Malinke. Staatliche Museen zu Berlin.

(Bolokonondo)

Le nom de ce rythme provient du mouvement des mains lors de la danse (bolokonondo signifie »neuf mains«).

Rythme: cycle de 84 pulsations, subdivisé en 7 groupes de 12 pulsations.

Keita, Mamady. 1992. Nankama. Fonti Musicali, FMD 195.

(Kadan — Bolo Könöndö)

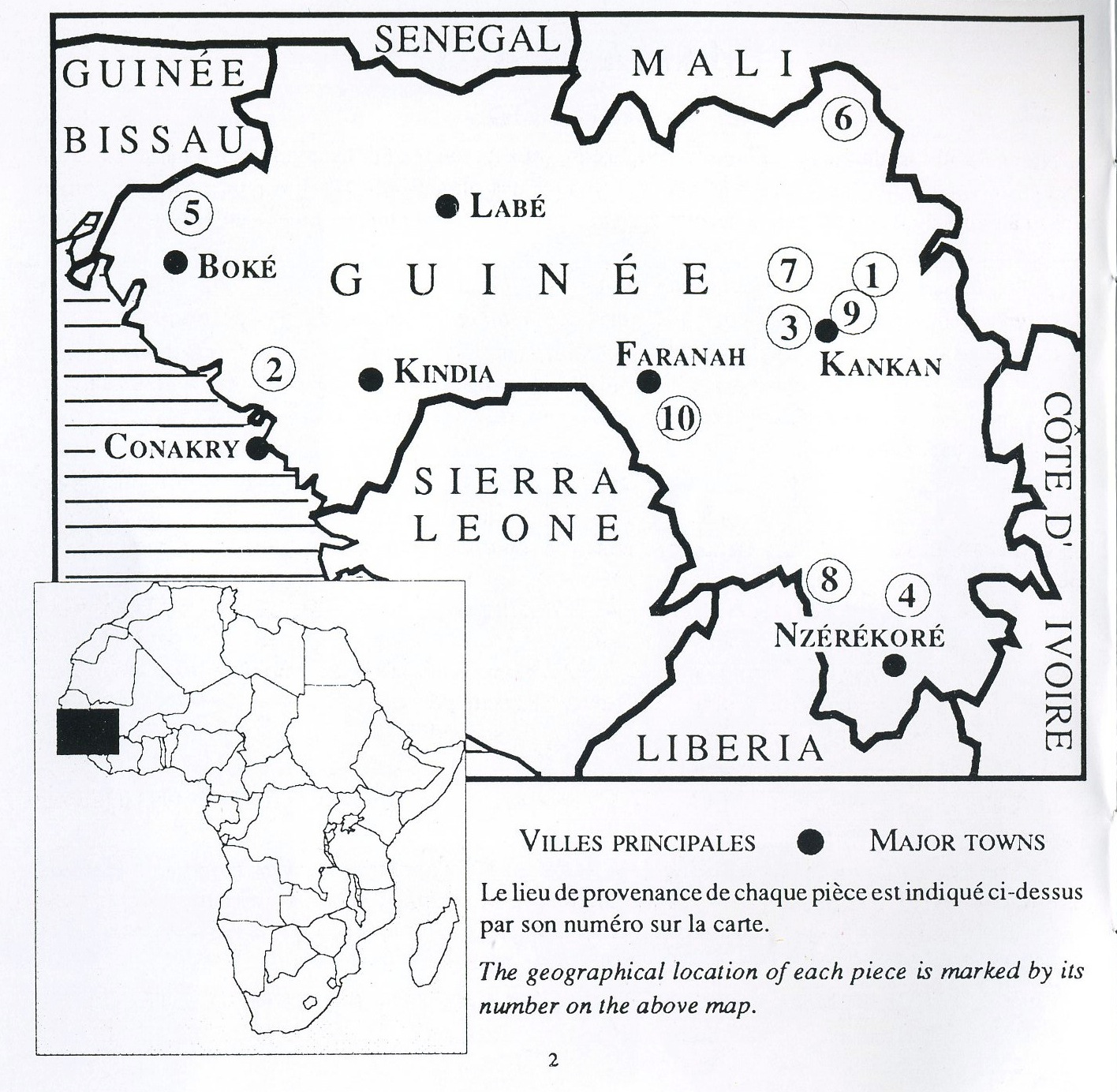

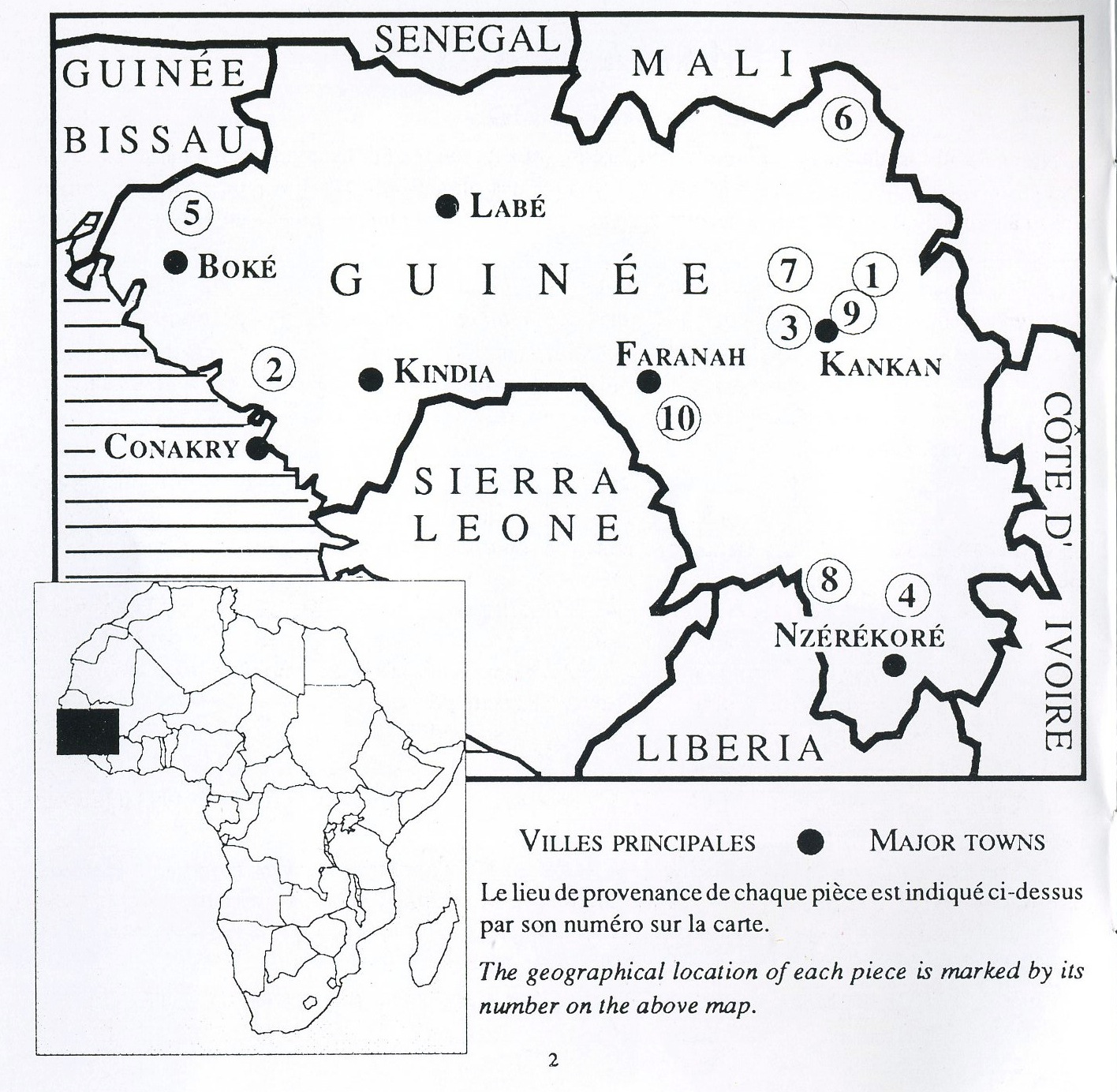

Régions: Kankan, Kouroussa, Siguiri. Rythme: Malenke (no. 7 on map.)

Joué pour les jeunes gens lors de l'épreuve de la force, du courage et de la fierté appelée couramment "danse des hommes forts".

Forè Foté. 1999. Wonberé: Music and Dance in Black and White.

(Bolo könöndö)

"Nine fingers," also in reference to the structure of the dance.

Camio, Mansa. 2006. An Bada Sofoli: Malinké Dunun Music of Upper Guinea. Middle Path Media, MPM 001.

(Bolokonondo)

The "Nine Paths," referring to the part played by the sangban. Djakoli Solo was a great dancer from Baro. He is remembered in this song.

| Ka wodi kè m’bolo | If I had money |

| Gnadi Djakoli Solo man | I would give it [sic] Djakoli Solo |

| Nan Djaka dén kèradi | Like his mother Nan Djaka |

| Sara Djakoli Solola | Djakoli Solo is popular |

| Ka sani kè mbolo | If I had gold |

| Gnadi Djakoli Solo man | I would give it to Djakoli Solo |

| Nan Djaka dén kèradi | Like his mother Nan Djaka |

| Sara Djakoli Solola | Djakoli Solo is popular |

| Hé hé Djakoli Solola wo | Hé hé Djakoli Solola wo |

| Nan Djaka dèn kèradi | Like his mother Nan Djaka |

| Sara Djakoli Solola | Djakoli Solo is popular |

| Hé hé Djakoli Solola wo | Hé hé Djakoli Solola wo |

| Nan Djaka dèn kèradi | Like his mother Nan Djaka |

| Sara Djakoli Solola | Djakoli Solo is popular |

| Hé hé Djakoli Solola wo | Hé hé Djakoli Solola wo |

| Nan Djaka dén kèradi | Like his mother Nan Djaka |

| Sara Djakoli Solola | Djakoli Solo is popular |

Diaby, Mohamed. 2007. Ala Na Na. Mohamed Diaby.

(Bolokonondo)

From the Kouroussa region, it is part of the Dounoun Ba family of rhythms. The dance of the strong man.

Delbanco, Åge. 2012. West African Rhythms. Charleston, SC: Seven Hawk.

(Bolo Konondo)

Dununba rhythm from Hamanah region, Upper Guinea; the name means "nine fingers."

Demosoninkelen

Bangoura, Fode Seydou. 2005. Fakoly 1.

(Takonani et Demosonikelen)

Demosonikelen is a dance of sexual banter. The men tease the women who respond by mocking the prowess of the men, their drum sticks, and so forth. The Sagban and Doundoun "talk" back and forth to each other, creating a rhythm resembling the words "demosonikelen."

Delbanco, Åge. 2012. West African Rhythms. Charleston, SC: Seven Hawk.

(Demusoni Kelen)

Dununba rhythm from Hamanah region, Upper Guinea; the name means "young girl."

Diadi

Delbanco, Åge. 2012. West African Rhythms. Charleston, SC: Seven Hawk.

(Diadi)

Dununba rhythm from Upper Guinea. Diadi was a boy who perished in the revolution because his parents did not sacrifice a chicken when he went to war.

Donaba

Billmeier, Uschi. 1999. Mamady Keita: A Life For the Djembe—Traditional Rhythms of the Malinke. Engerda, Germany: Arun-Verlag.

(Donaba)

Donaba means "great (woman) dancer." It was the nickname of a woman from Famoudou Konate's village who was rewarded with this name for her incredibly imaginative dances. They dedicated a song to her that says, "Mariama, come and show us a new dance!"

Delbanco, Åge. 2012. West African Rhythms. Charleston, SC: Seven Hawk.

(Donaba)

A very old dununba rhythm from Hamanah region in Upper Guinea; the name means "great dancer."

Delbanco, Åge. 2012. West African Rhythms. Charleston, SC: Seven Hawk.

(N'fa Kaba / Donaba Modifié)

Dununba rhythm from Sambalala in the Hamanah region of Upper Guinea. N'fa means old man.

Dunungbé / Kon

Konate. Famoudou. 1988. Famoudou Konaté maître-djembé et l'Ensemble Hamana Dan Ba. Guinée: Percussions et chants malinké, Vol. 2. Buda, 1977832.

(Dunumgbé)

Dans le vaste répertoire des dunums (danse des hommes forts), Dunumgbé est le plus important pour Famoudou. Au village, durant sa jeunesse, Famoudou a pu faire l'expérience de la dureté des combats lorsqu'il accompagnait cette danse; c'est pourquoi il qualifie ce rythme de particulièrement agressif.

Konate, Famoudou. 1991. Rhythmen der Malinke. Staatliche Museen zu Berlin.

(Dununbè / Bada)

Comme il apparaît clairement dans la description de la fête dununba, dununbè est le plus important des rythmes de la catégorie dununba. Il est directement suivit par bada, un rythme de 12 pulsations que les tambours basses varient continuellement; celui-ci présente pour la danse une particularité: alors que tous les rythmes de 12 pulsations correspondant aux pas de danse sont réunis en 4 groupes de 3 (4 x 3), le bada apparait seul sous la forme de 3 groupes de 4 (3 x 4).

Rythme: cycle de 24 pulsations, subdivisé en 2 groupes de 12 pulsations.

Billmeier, Uschi. 1999. Mamady Keita: A Life For the Djembe—Traditional Rhythms of the Malinke. Engerda, Germany: Arun-Verlag.

(Dunungbe)

This is the oldest and most important rhythm of the Dununba family. It is called the "mother" of all Dununba rhythms and is played at the beginning of a festivity. Many other rhythms have developed from this one.

Camio, Mansa. 2006. An Bada Sofoli: Malinké Dunun Music of Upper Guinea. Middle Path Media, MPM 001.

(Kon)

Kon, or Dununbae, is considered the "mother of all dunun rhythms." Meaning that all of the other rhythms and dances that are part of the dunun family evolved from this one.

| Hé kon kan yé | Hé it's the Kon sound |

| Gberedouka la kon kan yé | The Kon of Gberedou |

| Hé hé mansaba yé | Hé hé big mansa yé |

| Möö baraké Gberedouka kilila | When you call the people of Gberedou |

| Möö té okon kaliyala | The Kon must not be fast |

| Hé hé mansaba yé | Hé hé big mansa yé |

| Hé kon kan yé | Hé it's the Kon sound |

| Hé it's the Kon sound | The Kon of Baro |

| Hé hé mansaba yé | Hé hé big mansa yé |

| Möö baraké Baroka kilila | When you call the people of Baro |

| Möö té okon kaliyala | The Kon must not be fast |

| Hé hé mansaba yé | Hé hé big mansa yé |

| Hé kon kan yé | Hé it's the Kon sound |

| Barati la kon kan yé | The Kon of Barati |

| Hé hé mansaba yé | Hé hé big mansa yé |

| Möö baraké Barati coura kilila | When you call the new Barati |

| Möö té okon kaliyala | The Kon mustn't be fast |

| Hé hé mansaba yé | Hé hé big mansa yé |

Diaby, Mohamed. 2007. Ala Na Na. Mohamed Diaby.

(Dununbè)

A Malinke rythm from the Kouroussa area. The dance of the strong man.

Bangoura, M'Bemba. 2011. Wamato: Everybody Look! Featuring Master Drummer, M'bemba Bangoura. Vol. 2. Wula Drum Inc.

(Dundungbe)

Dundungbe comes from the Dundunba family. It comes from Kouroussa [Guinea]. Dundunba has so many rhythms, but it has only one accompaniment. Only one. We say slap, tone, slap. So for the second part and the third part the slap, slap, tone, tone, slap, and the bass djembe part, that's the Ballet [sic] [Africains] which improvised that. But if you go back to traditional, there's only one accompaniment you can see in Dundunba.

Delbanco, Åge. 2012. West African Rhythms. Charleston, SC: Seven Hawk.

(Dunun Gbè)

The mother of all dununba rhythms; the dance of the strong men, Upper Giunea [sic].

Delbanco, Åge. 2012. West African Rhythms. Charleston, SC: Seven Hawk.

(Kon Masi)

A variation played once in the beginning of Dunun Gbè in the village of Baro.

Gbada

Konate. Famoudou. 1988. Famoudou Konaté maître-djembé et l'Ensemble Hamana Dan Ba. Guinée: Percussions et chants malinké, Vol. 2. Buda, 1977832.

(Gbada Wewe)

Gbada désigne un petit serpent noir très venimeux. C’est un morceau complètement arrangé par Famoudou, mais inspiré des rythmes de la Guinée Forestière avec les krins, ainsi que du rythme de Dunum Gbada.

Konate, Famoudou. 1991. Rhythmen der Malinke. Staatliche Museen zu Berlin.

(Dununbè / Bada)

Comme il apparaît clairement dans la description de la fête dununba, dununbè est le plus important des rythmes de la catégorie dununba. Il est directement suivit par bada, un rythme de 12 pulsations que les tambours basses varient continuellement; celui-ci présente pour la danse une particularité: alors que tous les rythmes de 12 pulsations correspondant aux pas de danse sont réunis en 4 groupes de 3 (4 x 3), le bada apparait seul sous la forme de 3 groupes de 4 (3 x 4).

Rythme: cycle de 24 pulsations, subdivisé en 2 groupes de 12 pulsations.

Percussions de Guinée. 2002. Les Genies du Djembe. Konkoba Music.

(Gbada)

Origin: Kouroussa (Upper Guinea.)

After the harvest, the storage bins are full of grain. It is festival time in the village. Young men and young women gather in the public place to celebrate the good harvest. The surprising arrival of these Djembe girls are received by the young men who decide to challenge the new comers with series of tests. The talented girls' performance with their unique dexterity impresses and convinces the arrogant young men to allow them to enter the circle of the great Drummers of Gbada. Young people then praise the farmers' chief (Sene Samo) with a special tribute.

Delbanco, Åge. 2012. West African Rhythms. Charleston, SC: Seven Hawk.

(Bada)

This rhythm is used as transition [sic] between two other dununba rhythms (here with transition into Dunun Gbè.)

G'beredu

Camio, Mansa. 2006. An Bada Sofoli: Malinké Dunun Music of Upper Guinea. Middle Path Media, MPM 001.

(Gberedouka)

The people of Gberedou.

| Hé dönaba wo* | Hé great dancer |

| Gbereka dönan | Dancer of Gberedou |

| Dön coura labö hé | Create another dance |

| N'tola wourala doumounan | While having my dinner |

| N'tolo bilala dounoumba | I heard the sound of dununba |

| Gberedouka dönan | The great dancer of Gberedou |

| Bara dön coura labo hé | has created another dance |

Delbanco, Åge. 2012. West African Rhythms. Charleston, SC: Seven Hawk.

(G'beredu)

Dununba from Ousa region in Upper Guinea.

(G'bereduka)

A dununba rhythm played in the G'beredu region of Guinea.

Kadan

Konate. Famoudou. 1988. Famoudou Konaté maître-djembé et l'Ensemble Hamana Dan Ba. Guinée: Percussions et chants malinké, Vol. 1. Buda, 92727-2.

(Kadan)

This is one of many "Dunum" pieces (dances of strong men), but it is danced by the young "Bilakoros" (non-circumcised children.) "Kadan" (liana bracelet in Malinké), is both the name of these anklets (6 to 8 in number) and of the dance. The Bilakoros are the specialists of this dance, which people come and watch like a show. The anklets of the dancers clink against each other, while the phrases of the solo djembe, the dunumba and the sangban correspond to their steps.

"...here come the Bilakoros dancing the Kadan..."

Keita, Mamady. 1992. Nankama. Fonti Musicali, FMD 195.

(Kadan — Bolo Könöndö)

Régions: Kankan, Kouroussa, Siguiri. Rythme: Malenke (no. 7 on map.)

Joué pour les jeunes gens lors de l'épreuve de la force, du courage et de la fierté appelée couramment "danse des hommes forts".

Bangoura, Fode Seydou. 2005. Fakoly 1.

(Kadan)

Kadan are foot rattles that set the time for this dance. It is part of the ritual transition to adulthood performed by "Bilakoros," not yet circumcised boys. This song talks about an orphan crying because he doesn't have anyone.

Delbanco, Åge. 2012. West African Rhythms. Charleston, SC: Seven Hawk.

(Kadan)

Dununba rhythm from Upper Guinea, danced by the bilakoro (uncircumcised boys.)

Kedundun

Delbanco, Åge. 2012. West African Rhythms. Charleston, SC: Seven Hawk.

(Kedundun)

Dununba rhythm played after the circle dance for the competitive dance solos.

Konkoba Dunun

Delbanco, Åge. 2012. West African Rhythms. Charleston, SC: Seven Hawk.

(Konkoba Dunun)

Dununba rhythm from Upper Guinea.

Könöwulen

Billmeier, Uschi. 1999. Mamady Keita: A Life For the Djembe—Traditional Rhythms of the Malinke. Engerda, Germany: Arun-Verlag.

(Könöwulen)

This rhythm is dedicated to a rich and strong man. Since his name was not supposed to fall into oblivion, the griots sing for him, "Thanks to your mother you became the man you are."

Delbanco, Åge. 2012. West African Rhythms. Charleston, SC: Seven Hawk.

(Konowulen)

Dununba rhythm from the Hamanah region of Upper Guinea.

Kurabadon

Billmeier, Uschi. 1999. Mamady Keita: A Life For the Djembe—Traditional Rhythms of the Malinke. Engerda, Germany: Arun-Verlag.

(Kurabadon)

This term means "sacred grove." The people come and worship the spirit that lives in this grove. They bring offerings and ask questions, for instance, about their family, business, hunting, and other matters. The procession to the sacred grove is accompanied by this rhythm.

Camio, Mansa. 2006. An Bada Sofoli: Malinké Dunun Music of Upper Guinea. Middle Path Media, MPM 001.

(Koudabadon)

Koudabadon is danced in the sacred forest of Baro. infertile women come from all over Guinea to ask Bando Fariman and Bolé Fadima (the feminine and masculine spirits that reside within the forest) for children.

| Nankouda! | New mothers, |

| koudaba don lamada | The dance of the new mothers has begun |

| Hé | Hé |

| Kodi nankouda | What did you say, new mothers? |

| Hé n'to lamada hé | Hé my name has been honored |

| Baroka | People of Baro |

| lu nani dén ko léro | I came for children |

| Kodi nankouda | What did you say, new mothers? |

| Koudaba don lamada hé | The dance of new mothers has begun |

Delbanco, Åge. 2012. West African Rhythms. Charleston, SC: Seven Hawk.

(Kurabadon)

Dununba rhythm from Upper Guinea.

Nantalomba

Keita, Mamady. 1995. Mögöbalu. Fonti Musicali, FMD 205.

(Nantalomba)

A song of provocation and insults of the baratingi, the oldest of the young people in the village, towards the baradögöno or younger ones. The youngest are compared to a spider with its legs pulled off called Nantalomba to get them to fight.

The baratingi consider themselves as being the true owners of the bara (space for dancing) and the challenges between the the different age-groups occur when the dances take place. The circles that correspond to each age group are laid out concentrically around the tree planted in the middle of the bara. The leader carries a decorated hatchet called djendé and a manin fösson, a riding crop braided from hippopotamus skin.

When one of the younger boys wishes to join the group of older boys, he moves out of his own circle and dances backwards. He meets the leader of the other group, who asks him "The way?", to which he answers "It is marked on the back!" A reciprocal flagellation then follows, that leads either to the boy's acceptance or rejection by the older group when the men who are present, appreciating the boy's courage, put a stop to the test.

| Nantalomba, ééé | O you, Nantalomba, |

| I badaban ikoudoula banankou too dö woo. | Since you have stuffed yourself with manioc paste, |

| Idö wolo kognouma ééé | Dance now as you must! |

Billmeier, Uschi. 1999. Mamady Keita: A Life For the Djembe—Traditional Rhythms of the Malinke. Engerda, Germany: Arun-Verlag.

(Nantalomba)

Nantalomba is a popular dance, and also a song in which the younger dancers are compared to a spider.

Delbanco, Åge. 2012. West African Rhythms. Charleston, SC: Seven Hawk.

(Nantalomba)

Dununba rhythm from Upper Guinea. The oldest of the boys (baratingi) insult the younger boys (baradogono) and if one of them tries to join the older, his courage is tested in reciprocal flagellation.

Taama

Konate. Famoudou. 1988. Famoudou Konaté maître-djembé et l'Ensemble Hamana Dan Ba. Guinée: Percussions et chants malinké, Vol. 2. Buda, 1977832.

(Taama)

Taama is a Dunum (dance of the strong men) rhythm that evokes the dancers stepping, turning around, stopping and starting to walk again.

Forè Foté. 1999. Wonberé: Music and Dance in Black and White.

(Taama)

Meaning "to walk like the people of Hamanah."

Delbanco, Åge. 2012. West African Rhythms. Charleston, SC: Seven Hawk.

(Taama)

Dununba rhythm from Upper Guinea.

Takonani

Konate. Famoudou. 1988. Famoudou Konaté maître-djembé et l'Ensemble Hamana Dan Ba. Guinée: Percussions et chants malinké, Vol. 1. Buda, 92727-2.

(Takonani)

Il appartient également à la famille des Dunums. "Takonani" signifie "prendre quatre fois", en référence au pas de danse. Ce rythme qu'affectionne particulièrement Famoudou, l'inspire beaucoup. Il commence le morceau sur un djembé et le poursuit sur un autre d'une tonalité différente. Il nous montre ainsi toutes les nouances et la variété des phrasés qu'il peut développer sur son instrument.

Keita, Mamady. 1996. Hamana. Fonti Musicali, FMD 211.

(Takonani)

The name of this rhythm goes with the dancers' steps as they perform the same movement four times. The order of the solo is Mamady/ Famoudou.

Bangoura, Fode Seydou. 2005. Fakoly 1.

(Takonani et Demosonikelen)

Takonani means "Take Four Time" rhythm.

Delbanco, Åge. 2012. West African Rhythms. Charleston, SC: Seven Hawk.

(Takonani)

Dununba rhythm from Upper Guinea; takonani means "four moves," referring to the dance steps.

Takosaba

Konate, Famoudou. 1991. Rhythmen der Malinke. Staatliche Museen zu Berlin.

(Takosaba)

Le nom est dérivé des trois plus importants mouvements de danse, qui sont exécutés pendant les trois premières 12 pulsations.

Rythme: cycle de 60 pulsations, subdivisé en 5 groupes de 12 pulsations.

Billmeier, Uschi. 1999. Mamady Keita: A Life For the Djembe—Traditional Rhythms of the Malinke. Engerda, Germany: Arun-Verlag.

(Takosaba)

This term means "three times" and refers to the movements of the dance, which repeat three times.

Forè Foté. 1999. Wonberé: Music and Dance in Black and White.

(Takosaba)

Literally, "Take three," referring to a movement at the beginning of the dance.

Delbanco, Åge. 2012. West African Rhythms. Charleston, SC: Seven Hawk.

(Takosaba)

Dununba rhythm from Upper Guinea; takosaba means "three moves," referring to the dance steps.

see also:

Chevalier, Laurent, dir. 1994. L'enfant noir. Primafilm.