soboninkun

(Sogoninkoun)

p. 215

Il y a plusieurs masques récréatifs, les thèmes et les sujets varient pour ainsi dire à l'infini, d'une région à une autre ou même parfois d'un village à un autre. . . . Les Malinkés et les Bambaras exhibent le Konden et le Sogoninkoun, masques à représentation animale. . . . Les nombreuses occasions de fête en saison sèche font des masques des êtres familiers du folklore : l'annonce de l'appartition du Sbondel, du Konden ou du Sogoninkoun est un événement heureux, que les jeunes gens attendent avec impatience. Ainsi les masques récréatifs constituent un élément central de la vie culturelle villageoise.

p. 216

Le Sogoninkoun, masque de réjouissance populaire, est absolument profane ; par le style, ce haut de masque est de la même veine que le Tyi-wara : la sculpture représente l'antilope, la biche et une statuette de jeune fille ; les trois sujets sont combinés avec on ne peut plus de bonheur ; les lignes sont pures, l'ensemble judicieusement équilibré réalise la gageure de représenter trois sujets en une sculpture haute d'à peine 30 centimètres. La danse de Sogoninkoun évoque les cabrioles et les ébats amoureux de l'antilope dans les hautes herbes de la savanne, danse véritablement acrobatique adoptée par les Peuls mandinguisés du Wassoulou (Manding oriental).

Sogoninkoun : haut de masque profane pour danses de réjouissances publiques chez les Bambaras et les Wassoulounkées.

McNaughton, Patrick R. 1988. The Mande Blacksmiths: Knowledge, Power, and Art in West Africa. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

(Sogonikun)

p. 107

. . . a finely forged sculpture of a female antelope with a baby on its back, another type of "little animal head" used in the youth and agricultural associations (Ill. 48).

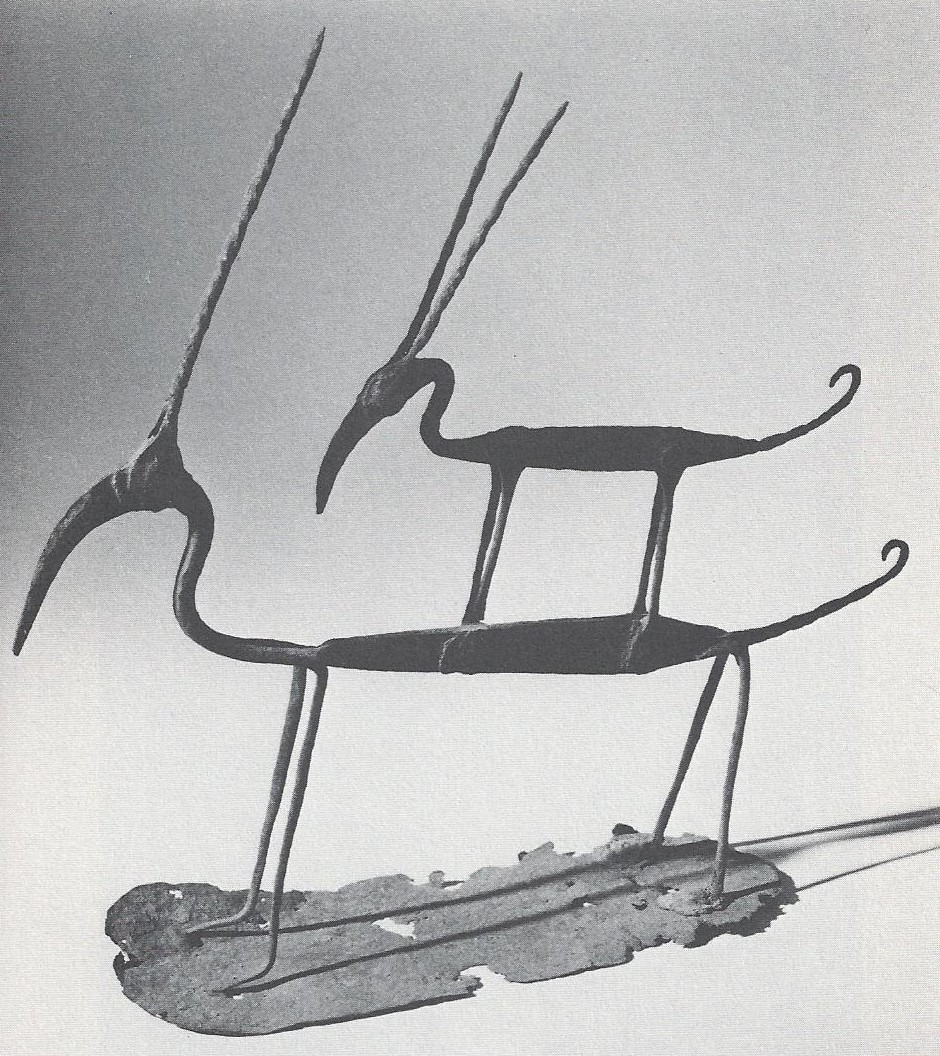

Plate 48. Southern Bamana forged iron antelope headdress (I. 141/8 in.). Private collection. Photographed by Jeffrey A. Wolin.

p. 111

Sogonikun, "little animal head," can be used to identify a variety of animal masks and headdresses, even though its precise application is to the masks and headdresses of a particular agricultural festival.

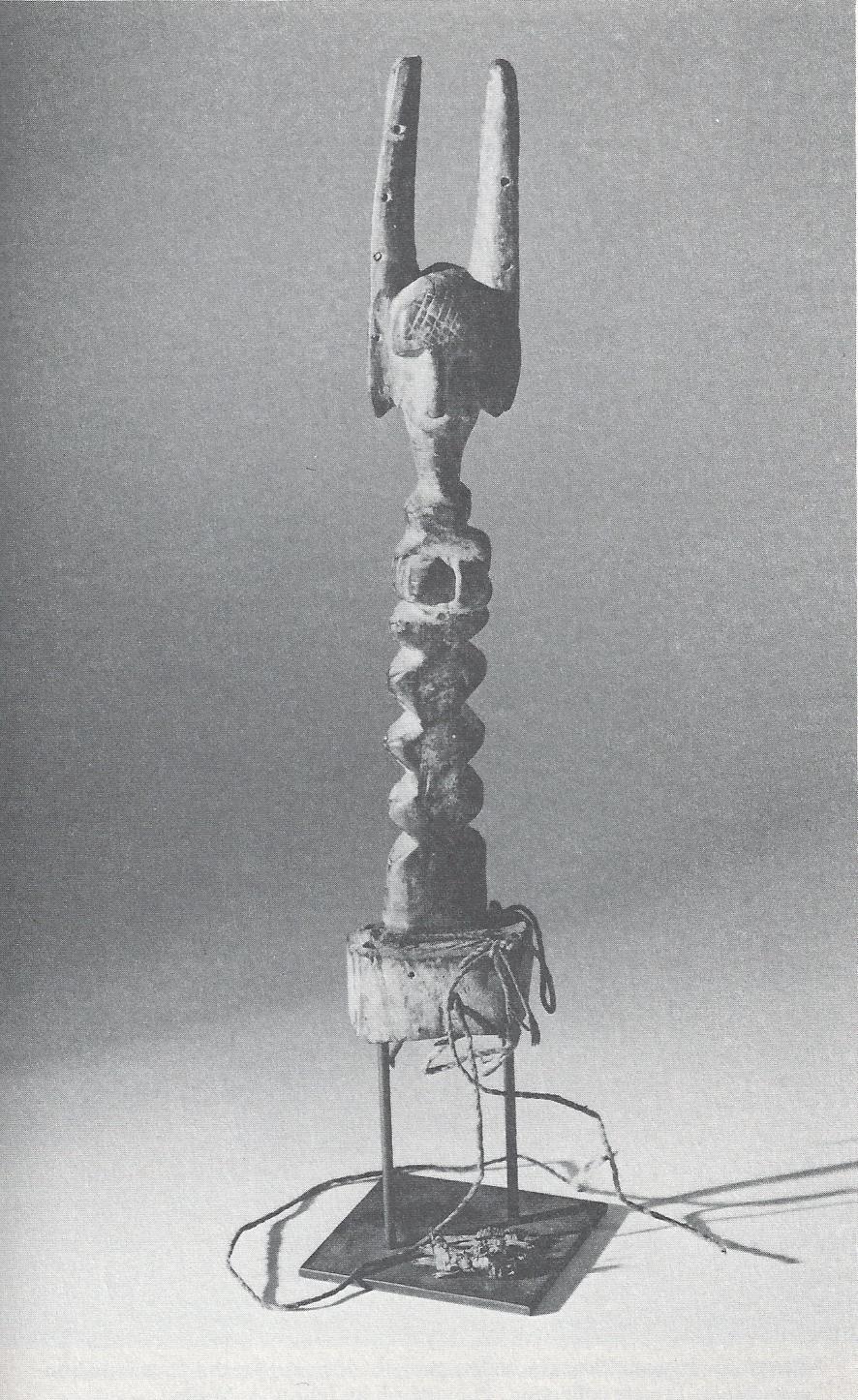

Plate 42. Southern Bamana carved wooden "little animal head" (h. 16 in.), designed to be mounted on a basketry cap strapped to a dancer's head. Private collection. Photograph by Jeffrey A. Wolin.

Keita, Mamady. 1989. Wassolon. Fonti Musicali, FMD 581159.

(Soboninkun)

Soboninkun est une danse de masque à tête d'animal. C'est toujours un initié au secret de ce masque qui la danse, au centre d'un gran van posé sur le sol.

| Dya n'di wa omori fe | Je vais avec Mory |

| Soboninkun Mory le | Mory qui porte le masque de Soboninkun |

| Dya n'di wa omori fe | Je pars avec Mory |

| Aiye |

Durán, Lucy. 1995. "Birds of Wasulu: Freedom of Expression and Expressions of Freedom in the Popular Music of Southern Mali." British Journal of Ethnomusicology 4: 101-34

(Sogoninkun)

p. 103

Sogoninkun is a masquerade . . . linked to festivities organised by age-set associations for agricultural cycles. These associations play a central role in Mande culture extending far beyond their original social contexts.6

6 See Meillassoux 1968b. Brenner, forthcoming, describes how these associations have been recreated as grin, a type of informal urban youth club.

p. 105

Samory Toure's military exploits are a subject of sogoninkun songs.11

11See Imperato's account of Sogoninkun (1981:46) and Meillassoux 1968b:99.

p. 113-15

Wassoulou performers attribute one of the roots of their music to a masquerade called sogoninkun, which has particular rhythms and singing styles (sogoninkunfoli). Sogoninkun "the little antelope head") is the most characteristic masquerade of the Wasulunke and the southern Bamana, originating in Wasulu (Fig. 4). It has been documented primarily by Prouteaux (1929), Meillassoux (1968a) and Imperato (1981), and is mentioned in passing by McNaughton (1988).

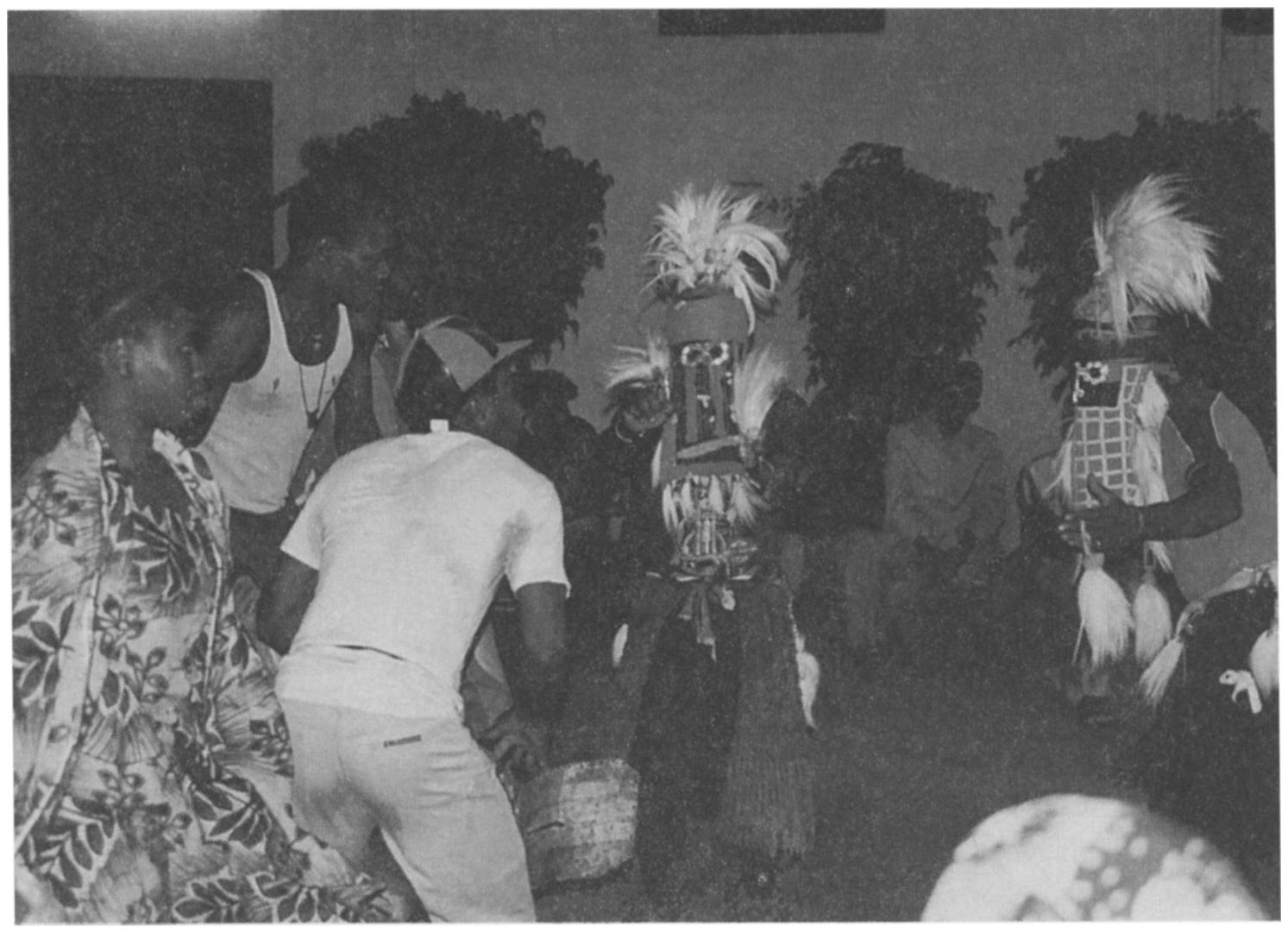

Fig. 4: Djembe player and sogoninkun dancers; child-naming ceremony, Bamako, 1995

Sogoninkun is one of many masquerades whose original context was the ageset association (ton). It is a fast-tempo masked dance performed by males accompanied only on the djembe and dundun (large cylindrical drum played with sticks). The lead singer (termed kono) is female as is the chorus.

Made of sculpted wood and heavy red or blue cotton cloth, the mask, which is said to represent a female antelope, covers the head completely, and hangs over the face, down to the chest, with small holes for the eyes. There is a white bushy (goathair) tail on top and smaller tufts of goathair attached to the sides of the face cloth. The masked dancers, wearing ankle rattles, interact with the drummers using powerful and supple acrobatic movements, described as those of a lion (a symbol of strength). Those who have the reputation of being great dancers, such as Amadu Ba (from Bougouni cercle), are sometimes called "sorcier danseurs" and they are said to "fly through the air" (Sali Sidibe interview). Women also perform the sogoninkun as a dance, but with graceful calm gestures (Diallo interview). The songs help to contextualise the masks and interpret their messages; the lyrics may refer to the prowess of certain animals and also to great heroes of the past. The dancers also interact with the singer: "the female soloist frequently places her hand on the sogoni koun [sic] dancer's shoulder, allaying his fears, slowly singing his praises..." (Imperato 1981:45).

Imperato states that sogoninkun is one of several "animal children" (wara deoun) masked dances performed for public entertainment, usually for agricultural festivities. He reports that while it has declined since the Second World War, "some very talented sogoni koun performers have become theatrical stars with audiences and reputations well beyond their local districts" (Imperato 1981:40).

Meillassoux's study of Bamako in the 1960s shows that migrant workers from Wasulu were a significant component of the city's population; he describes an "inter-ethnic" Bougouni association who performed sogoninkun and other masked dances. The masked dancers were "younger men between fourteen and twenty, who were born in Bougouni and live temporarily in town as seasonal workers, sometimes unemployed...between the appearances of the masks young men and even children of the association step in to perform yayoba, an acrobatic dance..." (Meillassoux 1968b:97, 99).

Nevertheless, Imperato's account of sogoninkun performances in Mali during the late 60s shows strong parallels with wassoulou. He describes how the singers addressed various messages to both dancers and audience; the young female soloist would "ask everyone's forgiveness, for herself and the troupe, for any direct or indirect insults that may inadvertently arise during her singing...[because] she is young and like all young people is capable of committing errors".30 He also recounts an event in which one (female) singer openly ridiculed a European in the audience who was trying to record the performance, satirising first him as an individual, and then Europeans in general: "Hey big fat white man/you in the shorts/you with grey hair and glasses/I see your red shirt/your white socks/that stick you are hiding/it is a microphone..." (Imperato 1981:46).

Sogoninkun and other masked dances disappeared during the radical measures of Modibo Keita's regime prior to his overthrow in 1968, and thereafter went into a decline (Imperato 1981). The severe droughts that Mali suffered have also taken their toll on traditions associated with the agricultural cycle. Nevertheless sogoninkun continues to be performed as a masked dance among Wasulunke both in the region and in Bamako, at weddings and circumcision celebrations, but not in the context of wassoulou music, where it was recreated as a rhythm and style of singing.31

Nevertheless, many of the early wassoulou artists of the 1960s and '70s such as the late female singer Kagbe Sidibe, started out as sogoninkun singers. Abdoulaye Diabate, a popular singer originally from Segou, but now based in Koutiala, who incorporates wassoulou styles into his recordings, has a song entitled Sogoninkun, in which he celebrates the tradition. One of the most influential singers of wassoulou, Coumba Sidibe, is also widely associated with sogoninkun; her father was reputed to be a great exponent of the dance.32

32 See her compact disc Sanghan, sleeve notes: "son père était un sorcier danseur du Sokoninkou, toujours du grand Wassoulou".

p. 122

Wassoulou first emerged as a named style in the years just after independence, and appears to have been created when sogoninkun singers such as (the late) Kagbe Sidibe began to record for Radio Mali. Whereas sogoninkun was originally accompanied only on drums, Kagbe Sidibe and others began to include the kamalengoni and electric guitars in their ensembles.

The first recordings date from the 1960s, but otherwise little information is available on this early phase. Wassoulou at this point was not widespread, and may have been eclipsed by Bamako's sogoninkun associations.

p. 127

Oumou Sangare [was] born in Bamako, with a family background in Wasulu (her parents are from Medina Diassa in Yanfolila and her mother is a sogoninkun singer).

Billmeier, Uschi. 1999. Mamady Keita: A Life For the Djembe—Traditional Rhythms of the Malinke. Engerda, Germany: Arun-Verlag.

(Sobonikun)

Traditional Ethnic Group: Malinke; Wassolon Region

Soboninkun is the name of a mask representing a small animal's head. It is the very special dance of the man who wears this mask. He performs with it an elegant dance that requires much skill and a good sense of balance. The man dances on a huge sieve that normally is used to sift grains.

This dance is performed after the big harvest. A dancer who is especially good tours the entire region, accompanied by a griot and several drummers.

To dance Soboninkun, one must be initiated and know the secrets and rules of the dance intimately. One must also be in excellent physical condition in order to perform these artistic maneuvers. [sic] He is not always a professional, unlike the ballet dancers in the capital, and he has another job for his livelihood.

The dance lasts for several hours, and, as a reward for his performance, the dancer receives gifts and food items. To this day, Soboninkun is played exclusively for this special reason.

Zanetti, Vincent. 1999. "Les maîtres du jembe: Entretiens avec Fadouba Oularé, Famoudou Konaté, Mamady Keïta et Soungalo Coulibaly." Cahiers de musiques traditionnelles 12: 175-195.

(Soboninkun)

p. 181

Nous, on connaît le fond, on sait pourquoi et à quelle occasion on joue tel rythme : au Wassolon, à Siguiri, le rythme du soboninkun . . .

Charry, Eric. 2000. Mande Music: Traditional and Modern Music of the Maninka and Mandinka of Western Africa. Chicago; London: University of Chicago Press.

(Sogonikun)

p. 199

(See Charry, 2000.) (Table 12 Occasions for Drum and Dance Events.)

p. 207

Jow and tonw possess wooden masks, which are instantly recognizable emblems for their associations. The masks can take the form of elaborate vertical headdresses, face masks, or helmets that project horizontally. . . . Usually only the masks of tonw are taken out in public and danced in open performances. Well-known masks include those from the children's ton Ntomo (Zahan 1960), the agriculturally centered tonw Ciwara (Tyiwara) and Sogonikun (Sogoninkun) (Imperato 1981), and the most widespread of the jow, Kòmò (McNaughton 1970; Brett-Smith 1994).10

p. 209

Although is is not a major occupation, drummers are sometimes called on to encourage the work of clearing fields for planting or of weeding and to animate general fertility rituals. Jembe rhythms specific to this kind of work are Kassa (Mamady Keita 1989-disc:6, Chevalier 1991-vid)) and Sogonikun (Meillassoux 1968b:96–100). . . .

Drumming can accompany the dancing of the famous Bamana antelope head Ciwara masks that celebrate the initial breaking up of the soil for planting (Brett-Smith 1994:34). Wara refers to a lion, but it can also refer to any animal with claws that scratch, hence the symbolism of scratching the earth. In Wasulu another mask, called Sogonikun (Sogoninkun), is used for similar purposes. Meillassoux (1968b:96–100) has described a dance association in Bamako named after the Sogonikun mask, made up of seasonal workers from Bougouni in Wasulu territory. Their dancing was accompanied by a jembe and a gangan (tama-like drum). Sogonikun is still danced in Bamako, and is an important component in the Wasulu sound, a recent genre in Malian popular music (Durán 1995a:113–15).13

13. Joyeux (1910:56–58, 1924:209–10) described an association called Koucikoroni whose purpose was to encourage agricultural labor with music. In a separate ceremony members would perform a special dance around a fire to the accompaniment of two jembes and one dunun.

Keita, Mamady. 2000. Balandugu Kan. Fonti Musicali, FMD 218.

(Soboninkun)

Soboninkun is the name not only of a dance, but also of its rhythm and of he who dances it in costume wearing the mask of a gazelle or other small animal.

| Aibö siyalaa wii mögöbulu sobodonkanyee | Clear the way! It's the sound that announces Sobo's arrival. |

Keita, Mamady. 2004. Sila Laka. Fonti Musicali, FMD 228.

(Soboninkun)

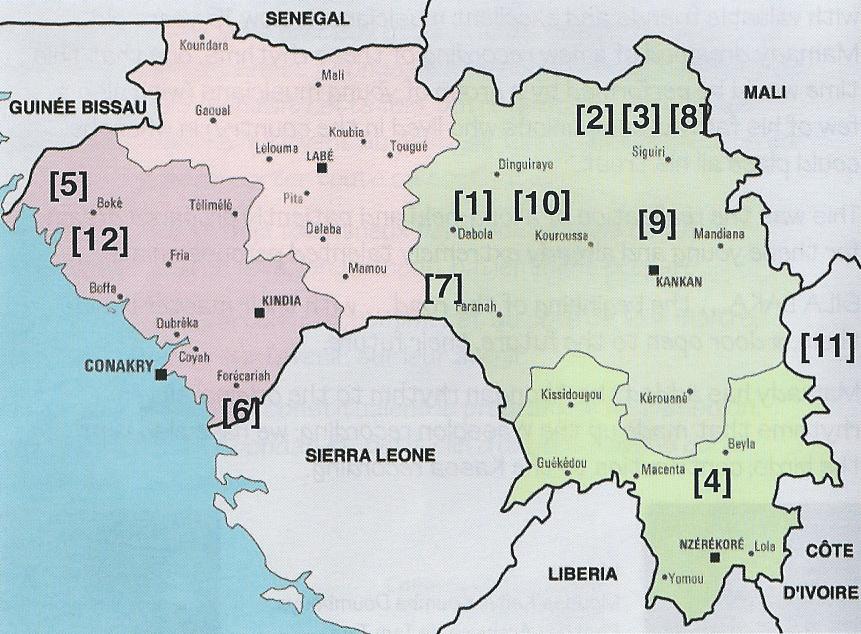

Soboninkun. Malinke. Région: Wassolon (no. 8 on map)

Soboninkun est une danse de masque à tête d'animal. C'est toujours un initié aux secrets de ce masque qui la danse, au centre d'un grand van posé sur le sol. Cette danse est exécutée à la fin des grandes récoltes. Le danseur arrive sur ls lieux de la fête accompagné par des batteurs. Il recevra des cadeaux, de la nourriture en récompense de sa prestation. Aujourd'hui encore, Soboninkun n'est dansé qu'à cette occasion.

| Mory le | ||

| Je vais avec Mory | Dya n'di wa omori fe | I am going with Mory |

| Mory qui porte le masque de Soboninkun | Soboninkun Mory le | Mory who wears the Soboninkun mask |

| Je pars avec Mory | Dya n'di wa omori fe | I am leaving with Mory |

| Aiye |

Traoré, Moussa. 2004. Mali Foli Dakan: Traditional Rhythms and Songs from Mali. Talking Drum, TDCD 80112.

(Sokonikou)

Sokonikou is a popular mask dance from the Wassolou region. The dance steps mimic movements of the antilope [sic].

Bangoura, Fode Seydou. 2005. Fakoly 1.

(Soboninkun)

Mask dances are a grand unity of percussion, dance, gesture and song. This rhythm is part of an animal-face mask ritual. The singers shame the evil person who can't get along with anyone.

Conde, Moussa "Bolokada." 2005. Morowaya. Abaraka Music, 107130.

(Soboninkun)

Soboninkum [sic] refers to the head of a small antelope-like animal called the kondani. Everybody loves the kondani because it's pretty and tastes good. When a hunter kills the kondani he comes into the village carrying the meat on his head.

| Soboninkun naninde E | Soboninkun has come, |

| Midi boni wularo naninde E | from very far away he has come |

Benkadi. 2006. Moné Mani. Leo Brooks, LB006.

(Soboninko)

This music is from a very particular mask dance that requires an initiate of the mask to perform. It is extremely demanding on the dancer, who performs the dance while standing in a flat basket that is used as a grain sieve.

Camara, Fode Moussa "Lavia." 2007. Bèmankan. Self-produced.

(Soboninkun)

From the region of Wassalon, Soboninkun is the name of a mask representing a small animal's head. It is the very special dance of the man who wears this mask. He performs with it an elegant dance that requires much skill and a good sense of balance. The man dances on a huge sieve that normally is used to sift grains. The dance is performed after the big harvest.